Access to all articles, new health classes, discounts in our store, and more!

Mouth Breathing: The SOMA Solution

The work of Weston A. Price, DDS, particularly his famous photographs of traditional peoples from around the world, highlights the broad, expansive faces of those individuals who thrived on the healthy diets of their ancestors. Their foods were rich in calcium and phosphorus, antioxidants, and other nutritional elements, in contrast to the oxidized, denatured, demineralized, and adulterated foods found in modern diets. The fat-soluble vitamins, A, D, E, and K – the latter of which is often considered to be Dr. Price’s activator X – were in ample supply. It has been clearly shown in Dr. Price’s research that it takes only one generation of poor diet to produce physical degeneration and mouth breathing. The long, thin faces; narrow dental arches; and crooked, overcrowded teeth of those people who adopted modern, deficient diets markedly contrasted with the broad, healthy faces and outstanding dentistry of those continuing to rely on their traditional foods.

In his dental practice, Dr. Price also developed one of the earliest, if not the first, appliances used to expand a patient’s underdeveloped maxillary arch (palate). In this case, his patient was a youth with Down’s syndrome. The palatal expansion he achieved resulted in rapid developmental changes that were both unexpected and profound.

Building upon these two concepts – the significance of our nutritional and cultural heritage, as represented in our dental architecture, and the attempt to restore full health through enlightened dentistry – has been my life’s mission. To this end, I have followed in the path of Dr. Price and others who, over the past seven decades, have developed dental appliances to restore healthy function, a goal that embraces, but also goes far beyond, cosmetic enhancement. Working in consultation with John Diamond, MD, past president of the International Academy of Preventive Medicine, I am now confident that a new level in therapeutic restoration of dental and overall health has been attained.

Overview of mouth breathing

We human beings are made to breathe through the nose. This is true even while we are resting or doing light exercise. Marathon runners, who run great distances with their mouths mostly shut, exemplify this. They breathe through the nose during most of their run, except perhaps for the last dash or immediately afterwards. This practice helps them to carry out aerobic respiration, which permits proper gas exchange in their lungs. Correct gas exchange, in turn, ensures the right level of water condensation within the body. Those runners who open their mouths early end up stressed before reaching the finish line. Not only will they fail to do well, they may not even finish the race. Their respiration will become anaerobic, and they will get dehydrated and worn out. Similar issues pervade the entire life of a mouth breather, from infancy to old age.

When a person breathes properly, the nose not only filters and warms the inhaled air but also humidifies it. As air passes through the sinuses, a thermal transfer takes place in which the air gets warmer and the sinuses get cooler. This is true particularly for the sphenoid sinus (located behind the nose), which cools the pituitary gland. Overheating of the sinuses can be looked on as a form of sinusitis. An overheated pituitary gland can malfunction, disturbing the hormonal balance that is crucial to proper growth and development.

In addition, the sinuses produce nitric oxide, which is inhaled into the lungs when one breathes through the nose. Nitric oxide has vasodilating effects on the lungs and inhibits bacterial growth. It increases gas exchange by 10 percent and blood oxygen by 18 percent. Moreover, it has anti-inflammatory effects.

Often, mouth breathing is associated with congestion, and it makes one prone to colds, flu-like symptoms, sinusitis, allergies, middle ear problems, rhinorrhea (runny nose), and adenoiditis (inflammation of the adenoid glands). It is generally observed that adenoiditis flares up more frequently in the spring season, when pollen is abundant in the air. However, adenoiditis can occur at any time and in any place, and can tax the adrenals so acutely that patients get extremely exhausted.

• • •

Mouth breathing is meant to be a temporary measure necessary when the nasal passages are blocked or when a person is performing moderate to extreme exercise. Unfortunately, even in these situations, gas exchange still gets muddled up when mouth breathing is prolonged, creating all sorts of difficulties for the individual. The mouth breather tends to lose carbon dioxide too quickly, and this can contribute significantly to respiratory alkalosis, which may lead to more systemic biochemical imbalances.

In compensation for this excessive loss of carbon dioxide, only the upper third of the lungs is used, and the diaphragm remains mostly static, resulting in a kind of one-dimensional expansion of the chest. In contrast, normal breathing involves three-dimensional movement, in which the diaphragm contracts and moves downward and the lungs expand fully, including sideways. This, in turn, creates abdominal movement that is good for both the intestines and liver, which can otherwise become stagnant.

There are many additional hazards associated with mouth breathing. Hyperventilation, or overbreathing, is one danger, and another is obstruction of the airway, which can lead to choking at night. Also alarming is the fact that mouth breathing creates a state of anxiety in the individual. The Russian professor Konstantin P. Buteyko has conducted detailed studies on hyperventilation and has made a great contribution by introducing corrective breathing methods.

Several sleep-related disorders, including snoring and sleep apnea (interrupted breathing), are also linked to mouth breathing. Sleep apnea can cause cardiac repercussions or hypertension in adults. In children, it can lead to difficulties in concentrating and focusing, resulting in lower performance in academics and sports. As a rule, mouth breathing also increases bacterial proliferation in the mouth and produces bad breath. In some instances, bedwetting and sleepwalking are observed. Many primitive responses, such as the Moro reflex (a startle response generally present only in infants), may be maintained for too long, hindering development and growth.

Mouth breathing in the night is prone to create particularly serious consequences. During sleep, muscle tone is at its lowest, and the jaw muscles are likely to sag due to laxity. The jaw can become retruded (moved backward) and trapped due to poor dental occlusion and architecture. In addition, inflamed tonsils, a retruded tongue, or a collapsed airway can obstruct breathing, creating a negative pressure in the chest. This can even collapse the chest in young, developing individuals. The sternum literally gets sucked inward, according to Dr. Makoto Kikuchi from Tokyo. There is often snoring and choking. The chance of hypoxia (inadequate oxygen supply) or an apnea attack becomes alarmingly high.

• • •

Commonly, mouth breathing is perceived as an unattractive trait. This is partly on account of the open mouth and, in some cases, tongue protrusion, as well as the maxillary underdevelopment. Mouth breathing disturbs the facial and dental pattern of the individual significantly. Generally, it results in a high palate with narrow arches, or a deep bite with a retruded lower jaw, giving the person a convex profile and adenoid face (a “long” face with protruding nose and retruded chin). In the majority of cases where there is tongue protrusion, anterior open bite (front teeth open) or lateral open bite (back teeth open) is most likely to occur.

The person may be conspicuous for regressive habits such as thumb sucking, lip sucking, or tongue-thrust swallowing. In most of these cases, the thumb or a pacifier, blanket, or any other object serves as an orthotic that decompresses the temporomandibular joints (jaw joints, or TMJs). Certainly, in children, this is an ideal condition for the pathological eruption of teeth. In addition, it serves to maintain strain patterns from birthing traumas. This fundamental structural pathology invariably leads to altered muscle function as well as neurological impairment. As a result, considerable facial asymmetry may develop, along with further pathological eruption, as the body struggles to compensate in a natural effort to maintain balance.

It is interesting to realize that a human child doubles in height during the first three years of life, and this is a unique event never to subsequently occur. At birth, about 30 percent of craniofacial growth has occurred. By one year of age, 50 percent has been completed. By twelve, craniofacial growth is at 90 percent, and by eighteen, it has reached 100 percent. If nasal breathing is not taking place during this crucial growth phase, facial and structural deformity will almost certainly result. Some deformities are so severe that simple orthodontics cannot set them right, and, in most cases, these may require surgery at great cost and with much consequent morbidity. It is not an exaggeration to say that severe undiagnosed nasal obstruction could cause infant crib deaths, considered to be “of unknown origin.” Hence, the sooner mouth breathing is identified and corrected, and nasal breathing restored, the better.

Role of the tongue and facial muscles during infancy

In his book Swallow Right or Else, Daniel Garliner, DDS, explains that the tongue is a very strong, active muscle and, along with the lips and facial muscles, plays a significant role in correct breastfeeding, controlling the flow of milk from the nipple as it is squeezed between the tongue and hard palate. In the process, the palate broadens and expands, helping to correct the strain pattern imposed during birthing. At the same time, the infant can breathe easily, creating a very comfortable environment in which to grow and develop. This type of suckling produces balanced sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity and healthy immune response. When the infant is not feeding, the tongue is placed on the hard palate with the lips closed, and nasal breathing takes place.

While an infant is in the process of growth, many primitive reflexes get downregulated. This is also the period when the hardwiring of the central nervous system takes shape. However, if during this period, stress occurs and growth is stunted, the primitive reflexes may continue to prevail, delaying neurological development. After all, the priority of these reflexes is to sustain the life of the infant despite all adversities, irrespective of the situation.

Infant breathing abnormalities can occur for various reasons, such as when the mother’s diet is not satisfactory or the baby is bottle fed using an incorrect nipple, so that the infant is constrained from controlling the flow of milk. The flooding of milk in the infant’s mouth is similar to drowning. To stop itself from drowning, the baby involuntarily thrusts out its tongue, under unnatural stress. As a result, breathing gets interrupted, compelling the infant to swallow air, causing bloating and related distress. This triggers greater sympathetic nervous system activity, causing a decrease in digestive function that invariably leads to a Th2 (T-helper type 2 cell) dominance in the immune response. The outcome of a Th2-dominant response is inflammation, with mucous production, rash, and adenoid and tonsil problems. This can further compromise the airway of the infant, and it struggles to position its tongue so as to thwart choking.

From my observations, there are basically three possible tongue positions that an infant will adopt in order to compensate for these breathing abnormalities, as explained below.

- The tongue may be positioned near the lower jaw. In this case, the lower jaw develops, but the maxilla remains underdeveloped.

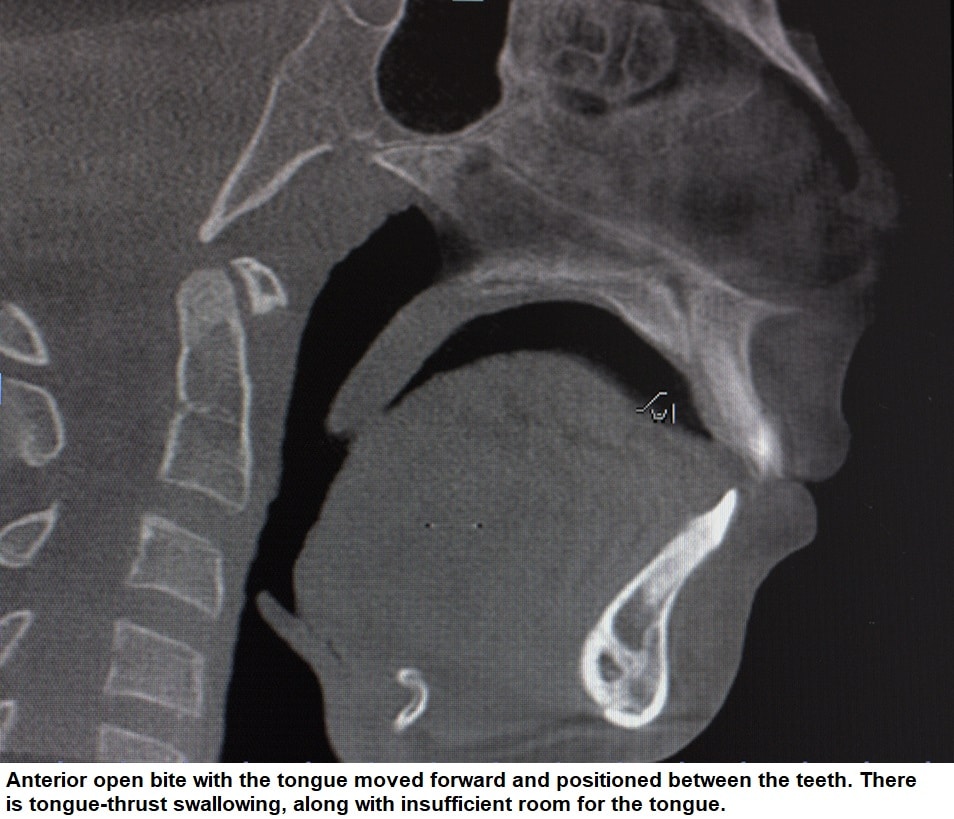

- The tongue may be placed between the teeth, producing an open bite.

- In the case of a protruding maxilla (overbite), the tongue may be placed on the palate, but there is still usually a strain pattern and TMJ pathology. Jaw clenching predominates, with or without tongue-thrust swallowing, as room for the tongue is limited. Instead of the tongue moving forward, it moves backward. Clenching is a way of holding the lower jaw to keep the tongue out of the airway.

Tongue-thrust swallowing further narrows the dental arches. In such cases, headaches and migraines may later arise. Breathing may be severely compromised, especially during the night. This may develop into a retruded jaw, promoting a forward-head posture during the day and leading to mouth breathing, mostly at night. Chewing, swallowing, and speaking are also affected by tongue positioning problems in all the above scenarios.

Dental and cranial considerations in mouth breathing

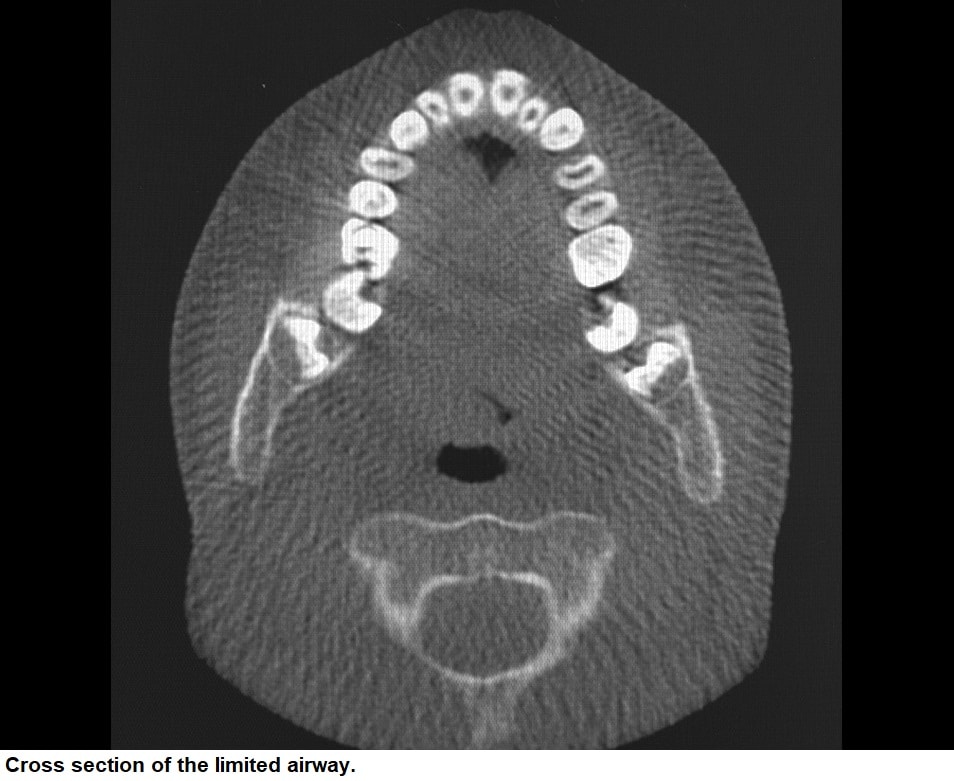

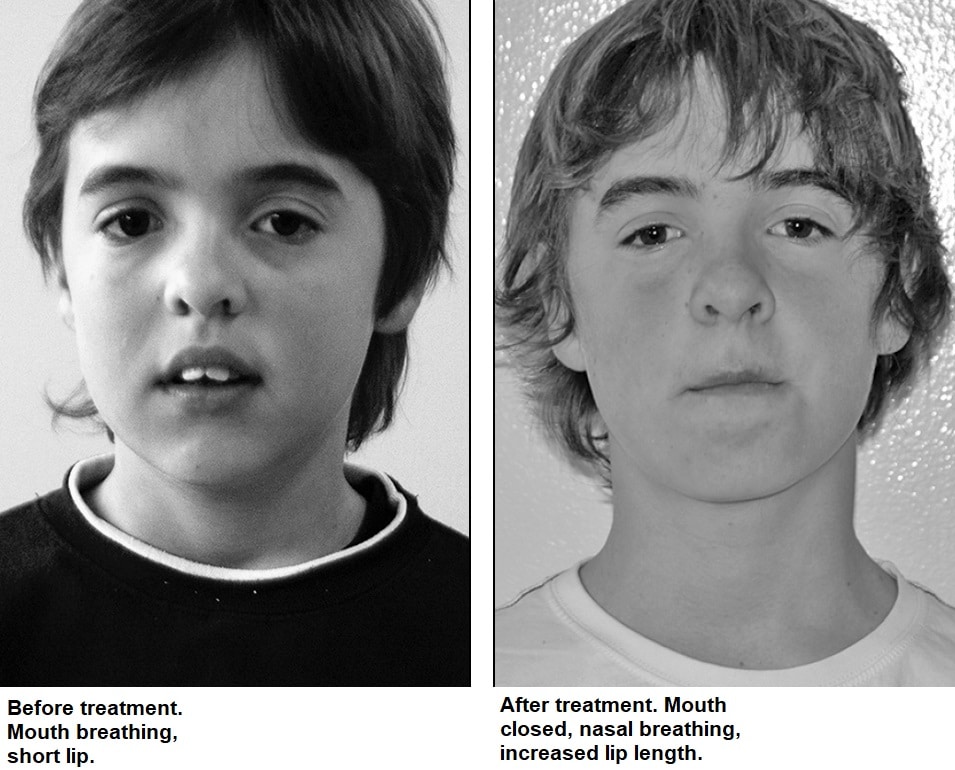

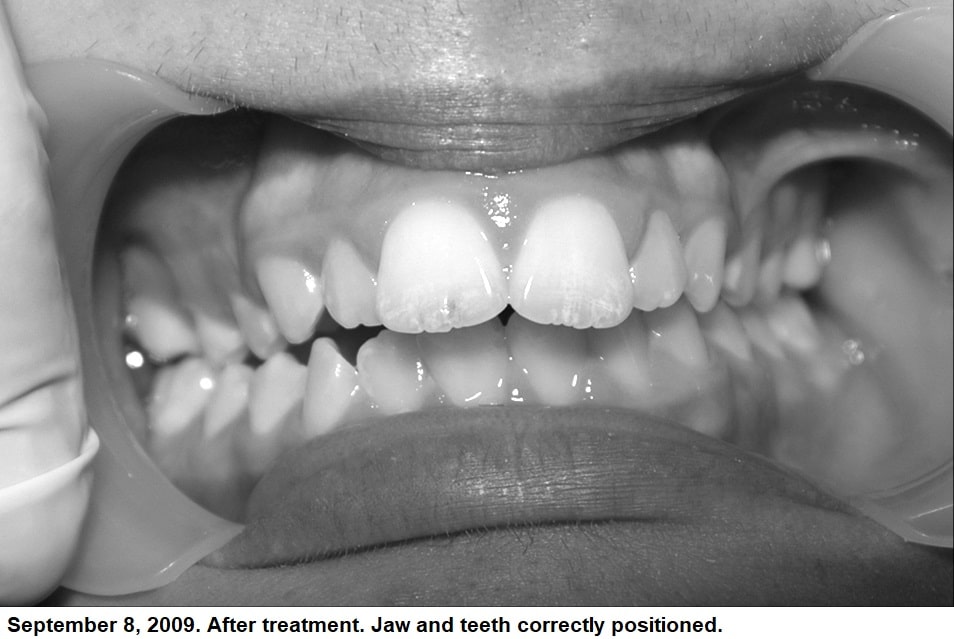

Close monitoring and proper attention to the sequential eruption of teeth during infancy and childhood are paramount to avoid poor occlusion and faulty architecture. They can also ensure proper jaw position, which indirectly or directly controls the airway passage by way of tongue position. Unattended faulty tongue position could lead to mouth breathing and pathological eruption of teeth. The following images illustrate these interrelated problems in one dental patient.

In order to address the cranial strain pattern associated with the developmental problems discussed previously, a combined approach by osteopaths, chiropractors, and dentists seems to make sense and should be a valuable area of future research. We do already know, however, that the sequential eruption of teeth and the cranial strain pattern are intimately linked.

We see today that a majority of orthodontic procedures are carried out without due consideration of the above-mentioned issues. More often than not, teeth are straightened without taking heed to correct the TMJ pathology and strain pattern. As a result, facial structure is narrowed rather than expanded. Thus, we end up with a narrower, crooked, mismatched face. Time and again, relapse takes place in such cases. Pain and discomfort can manifest as well. Extracting teeth unnecessarily and thereby making the tongue space smaller – common in treatment with orthodontic braces – is a sure recipe for future TMD (temporomandibular disorder) pain and sleep-disordered breathing.

Thankfully, there is greater awareness than ever before about the need to restore, precisely and correctly, the structure and function of the teeth in a timely fashion. There is general concurrence among researchers that this is one of the sure ways forward in solving the complex problem of mouth breathing. It should go without saying that there is a need to first understand and correct the existing pathology that drives the malocclusion. From the numerous cases addressed thus far, a valuable body of knowledge has been gathered, and it is being put to use successfully, bringing relief and permanent cure to many.

SOMA: Splint orthodontic myofunctional appliance

I have spent many years in research, refinement, and collaboration to develop an innovative mandibular advancement device that integrates splint, orthodontic, and myofunctional appliance (SOMA) therapy into one phase of treatment. The SOMA, which is patented in countries around the world, uses this multifaceted approach to treat TMJ pain and dysfunction and to restore overall health and normal function to individuals with poor dental architecture.

The SOMA treatment involves gentle expansion of bony structures in the upper palate without creating stress or pain. This produces major improvements in the facial pattern and straightens teeth, while pacifying the nervous system by dampening down sympathetic overdrive. Through its design, the SOMA avoids “fight-back” of facial muscles – the tendency to relapse into destructive muscle patterns – which may be produced by standard appliances. This aids orthodontic correction by greatly increasing efficiency. By reducing muscle fight-back, the SOMA can also effectively decompress the jaw joint and guide it into a stable, comfortable position to provide immediate relief of TMD.

The benefits produced by the SOMA are far more than just orthodontic and cosmetic. The SOMA has also helped relieve various types of chronic pain, respiratory issues, neck and spine problems, neurological dysfunctions, and immune system conditions. There is a hypothetical possibility that pituitary gland and pituitary-thyroid-adrenal axis functions improve when the cranium, through expansion of the maxillary arch, is widened. In addition, the SOMA creates more airway space, thus improving swallowing, breathing, speech, and sleep.

There are two common problems found in the use of standard fixed and removable dental appliances. The first problem is that standard appliances lock the maxillary sutures and teeth. If the cranial sutures are jammed, they inhibit the cranial respiratory impulse (CRI), the continuous pulsation in the skull whose strength is essential for optimum health. The second problem pertaining to many standard appliances is the use of metal across the midline of the palate. This is a major source of energetic stress that affects the CRI. According to Jerry Tennant, MD, metal is an “electron stealer,” and this property may possibly be the source of the energetic disruption.

The SOMA is able to avoid both of these problems due to its unique design. It creates sufficient orthodontic retention without jamming the cranial sutures, and its circular metal design does not stress the wearer. Also, a modified heat-cured or milled SOMA design incorporates a metal screw insulated with wax to eliminate energetic stress. The appliance avoids inhibition of the CRI and relaxes the muscles of mastication. When these muscles are relaxed, muscle fight-back does not occur around the bones of the face and jaw. This enables teeth to be orthodontically moved faster and without relapse. While, of course, it takes time to bring about changes in bone structure, one of the most interesting aspects of the SOMA is that as soon as the brain perceives the correct realigning pressure, there is an immediate reduction in stress and sympathetic nervous system overactivity. Moreover, there is enhancement of the CRI, opening of the nasal passages, and relief of muscle tension.

Although the SOMA was initially developed for treating TMD, it was found that the joint dysfunction would not resolve satisfactorily unless the malocclusion was also addressed. A cranial-orthodontic approach was incorporated into the treatment process as a second component. Unfortunately, this was not sufficient, and a third component needed to be added, which was adjustment of jaw (and tongue) position. Successful treatment could not be achieved unless a proper, stable jaw position was established with a sound cranial base. When these three components of treatment were addressed – that is, TMD correction, orthodontics, and establishment of a stable jaw position – highly satisfactory results were obtained in a short period of time. The SOMA device and protocol address all three components to provide rapid and effective TMD treatment, as well as a reduction in headaches, migraines, posture-related pain, and sleep-disordered breathing. This is a simple and intuitive treatment option for any dentist with background knowledge in TMD.

I credit John Diamond, MD, for his conceptual assistance and feedback in the design of the SOMA appliance and sharing his knowledge of holistic medicine, osteopathy, and his broad understanding of the importance of dentistry in looking at the total person. Collaborative work between myself and Dr. Diamond revealed that realignment of the cranial bones and forward positioning of the lower jaw are key factors that need to be addressed when dealing with the alignment of teeth. If the cranial structure and architecture are not corrected, the superficial dental realignment will collapse. By integrating splint therapy, orthodontics, and myofunctional treatment, the SOMA can help in the realignment process of the cranial base, establishing a sound foundation for a dental architecture from which teeth can be aligned and remain stable.

SOMA in action

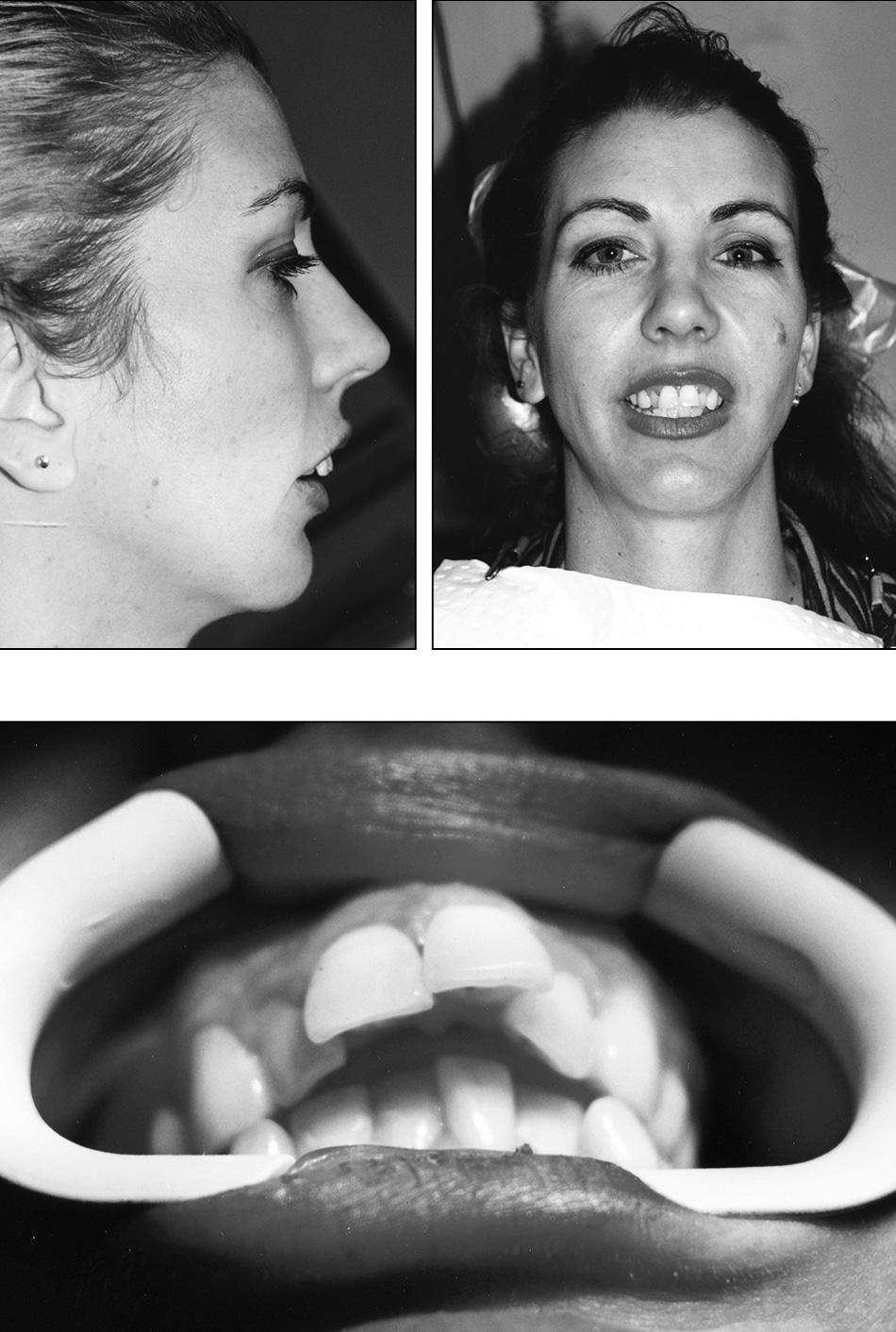

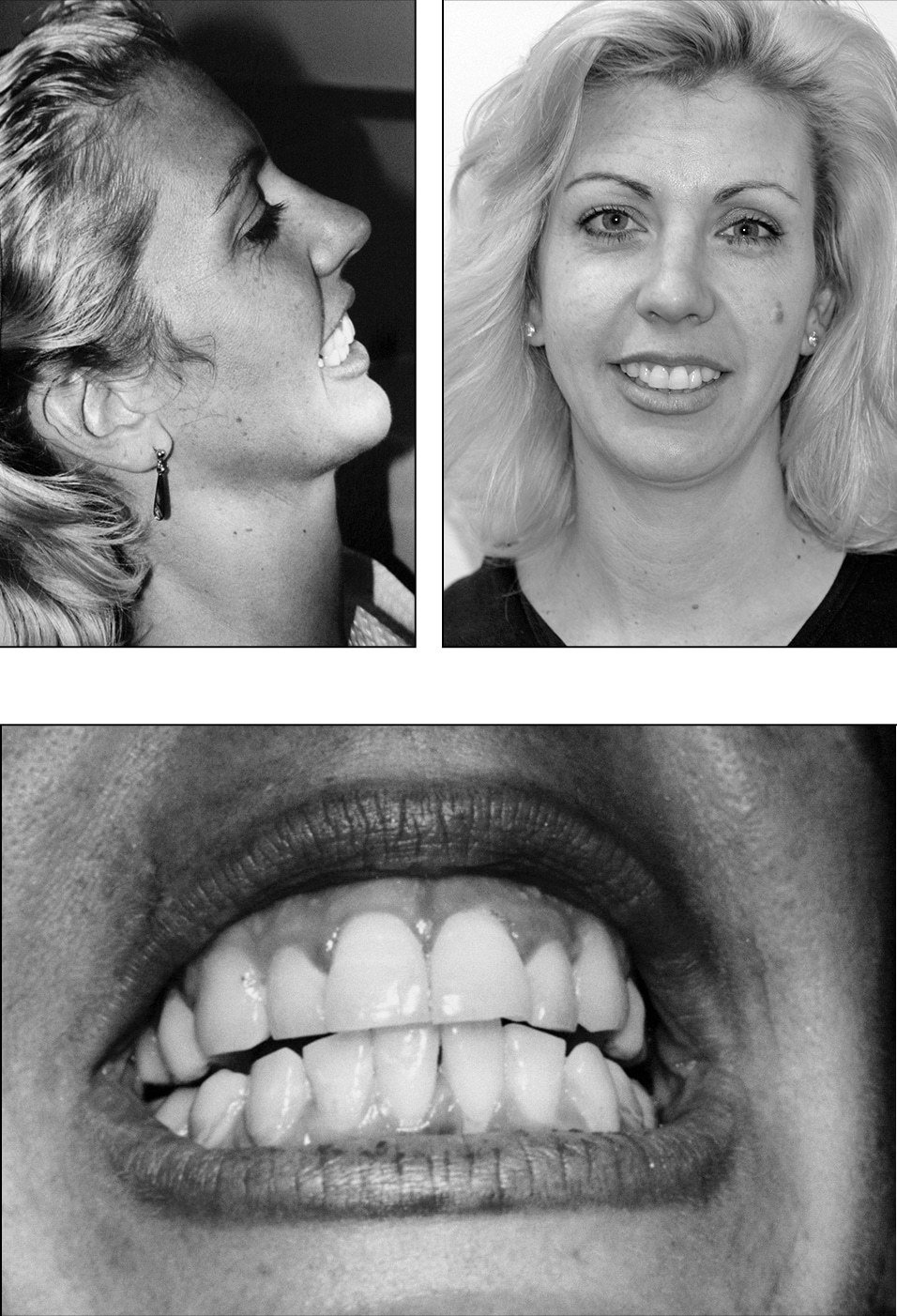

The following photos illustrate the case of Mrs. S., a patient who wore braces as a teenager to improve her smile. Unfortunately, her cosmetic improvement was reversed and the malocclusion re-established itself after the braces were removed. The patient’s relapse occurred because her braces did not address the underlying problems of her jaw position, breathing patterns, and orthopedic structure. These issues were accompanied by patterns of stress-related clenching and squeezing of facial muscles, along with severe migraines and neck and back pain.

Using SOMA treatment, the patient’s underlying problems were addressed while her teeth were being orthodontically corrected. After three months of wearing the SOMA, her lower jaw had moved forward, and she was able to comfortably close her mouth and breathe through her nose. In a year and a half, this method had provided her with a stable, correctly aligned smile and relief from her stress-related symptoms. I sometimes describe this process as the “unfolding of the face.” Her palate had widened, her teeth had straightened, and her neck and back pain had totally disappeared. Upon completing her treatment, Mrs. S. was completely relieved of her migraines and TMJ problem, and she now has a very beautiful smile.

Another successful treatment with SOMA

The following pictures illustrate the effectiveness of a threeyear dental correction using SOMA treatment and methodology for mouth breathing on a preteen with a 14 mm overjet (horizontal overlap of the upper front teeth over the lower front teeth). Advice on diet and nutrition was also provided.

See www.wholisticdentistry.com.au/case_ studies/index.html for many additional case studies demonstrating the effectiveness of the SOMA device and protocol.

A holistic philosophy

The current perception of the dental field by physicians and the broader community is narrow and does not reflect the true healing potential that dentistry can offer. A common understanding of dentistry is that it is a surgically focused approach to treatment, dealing with fillings, extractions, and the fitting of dentures. While these procedures do predominate in dentistry, treatment can have a much broader scope and impact. In fact, dentists can address conditions previously considered unrelated to dentistry. Associated structures that extend from the maxillofacial region have profound effects on the human body. One such structure, the trigeminal nerve, the largest of the cranial nerves, provides sensory feedback from the oral and facial regions of the head and, if compromised, can create a wide range of physiological and psychological pain conditions. For this reason, dentists can have a significant impact on human health through knowledge of the cranial sensory and motor nerves.

The potential influence dentistry can have on the functional neurology of the human body suggests that much collaborative work is needed between dentists and neurologists. Unfortunately, this is currently not the case, and, consequently, many dentists feel powerless to help patients in need of pain management. Too often, dentists are limited to observing health implications in the mouth exclusively. However, a growing number of dentists and doctors are recognizing the link between the mouth and the rest of the body. More extensive training of dentists and more collaborative work with physicians can potentially provide greater protective and earlier preventative care for patients.

Another change in approach that can limit harm to patients is reducing the unnecessary removal of teeth, especially maxillary premolars. Removal of key teeth in the maxillary arch for orthodontic treatment can contribute to the collapse of the maxilla and retrusion of the lower jaw. This can create a cascade of events leading to obstructive breathing problems and subclinical defects. From my experience, patients who present with obstructive airway breathing problems have a higher risk of other health-related issues, such as chronic fatigue syndrome.

Airway obstruction leads to breathing problems and subsequently affects sleep patterns. This has a profound influence on the body. Breathing problems are a form of stress that impede the body’s ability to handle other physiological and psychological stresses. When a person is unable to cope with stress, they are considered to be in survival mode. In this state, a person cannot effectively comprehend complex or difficult tasks. I believe that if a patient cannot breathe properly, they cannot think clearly. On the other hand, if a patient is able to breathe properly, they are able to think more clearly and perform more difficult tasks. These ideas relate to work by Dr. John Diamond. I have had the privilege to work closely with him on this topic, and we both believe improving the breathing patterns of patients can lead to a cascade of events that improve the overall health status of the patient’s quality of life.

My aim is to give dentistry its due importance by providing a whole-body approach to treatment, thus offering improved quality of care to patients. Holistic dentistry is a form of primary care for chronic as well as acute disease. It is multifactorial in its approach, and its effects influence every part and function of the person.

The SOMA device and protocol are tangible outcomes of this mission. They address primary developmental issues created by malnourishment, which can date from the earliest stages of conception and gestation. They also help compensate for poor maternal suckling or bottle feeding in infancy. Structurally, they help broaden both the dental palate and the overall face. Thus, emotionally, they help broaden the person and restore their birthright of health and happiness.

About the Author

Joseph Da Cruz, BDS, MDS, received his bachelor of dental surgery in 1976 and his masters in dental surgery in 1979, both from the University of Mumbai, India. He is board certified and is a member of the Australian Dental Association, a founding member of the Australian Society of Oral Medicine and Toxicology, a fellow of the Australian College of Nutrition and Environmental Medicine, and a member of the American and Australian Academy of Craniofacial Pain. He has over 41 years of clinical research and experience, integrating functional medicine and dentistry as a combined science. Dr. Da Cruz has lectured in Australia, India, China, Japan, and the US. He looks forward to teaching other dentists around the world about his innovative SOMA device and protocol. His website is www.wholisticdentistry.com.au.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Diamond J. Life Energy: Using the Meridians to Unlock the Hidden Power of Your Emotions. New York: Paragon House Publishers; 1990.

- Diamond J. Your Body Doesn’t Lie. New York: Warner Books; 1979.

- Garliner D. Swallow Right or Else. St Louis: Warren H. Green, Inc.; 1979.

- Lofstrand-Tidestrom B, Thilander B, Ahlqvist-Rastad J, Jakobsson O, Hultcrantz E. Breathing obstruction in relation to craniofacial and dental arch morphology in 4-year-old children. Eur J Orthod. 1999; 21(4):323-332.

- Miyazaki S, Kikuchi M. Oral appliance and craniofacial problems of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chapter 11 in Sleep Apnea and Snoring: Surgical and Non-Surgical Therapy. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- Mouth Breathing and Facial Deformity. Capitol Ear, Nose & Throat, P.A. Raleigh, NC. http://www.capitolent.net/mouth.htm. Accessed April 25, 2010.

- Oleski SL, Smith GH, Crow WT. Radiographic evidence of cranial bone mobility. Cranio. 2002; 20(1):34-38.

- Price WA. Nutrition and Physical Degeneration. 6th ed. La Mesa, CA: Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation; 2000.

- Samvat R, Osiecki H. Sleep, Health and Consciousness: A Physician’s Guide. Eagle Farm, Australia: BioConcepts; 2009.

- Simmons CH. Craniofacial Pain: A Handbook for Assessment, Diagnosis & Management. Chattanooga, TN: Chroma; 2010.

- Sutherland WG. The Cranial Bowl. Mankato, MN: Free Press Co.; 1986.

- Trevathan WR, Smith EO, McKenna JJ (eds.) Evolutionary Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999.

Published in the Price-Pottenger Journal of Health & Healing

Fall 2017 | Volume 41, Number 3

Copyright © 2017 Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation, Inc.®

All Rights Reserved Worldwide