Access to all articles, new health classes, discounts in our store, and more!

Vilhjálmur Stefánsson and the Fat of the Land

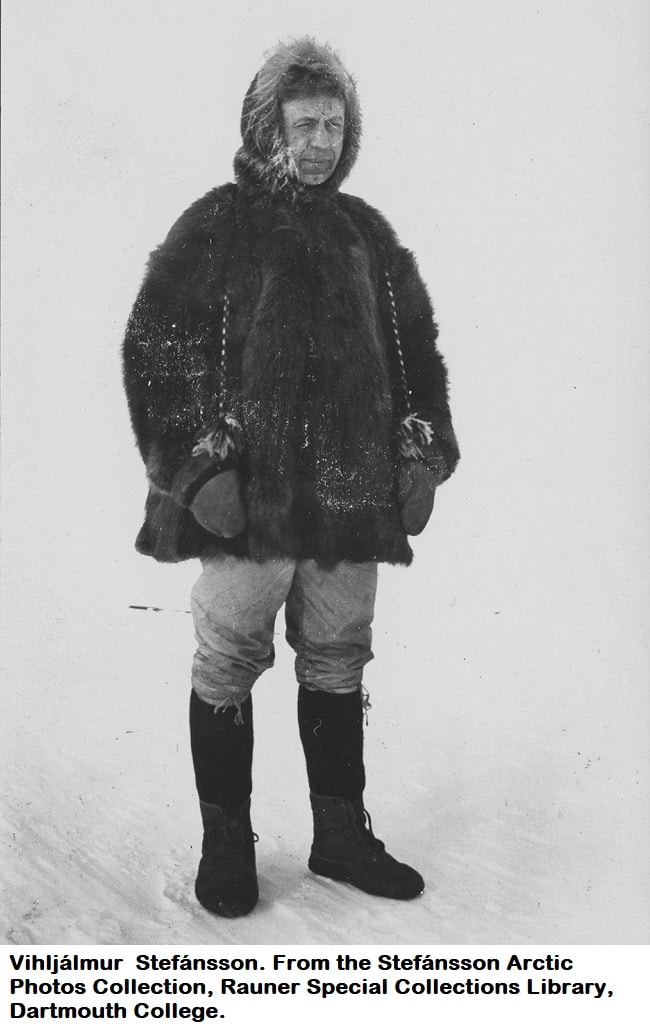

A Canadian of Icelandic parentage, Vilhjálmur Stefánsson (1879-1962) was a famed (and by some accounts, infamous) Arctic explorer purported to be quite possibly the first person of European descent to come into contact with native peoples of the North American Arctic. During the winter of 1906-1907, he was separated from the other members of his expedition, as well as his supplies. As fortune would have it, he was taken in by a group of Inuit he encountered on the Canadian Arctic coast. By the following spring, he had fully adopted their way of life, even having begun speaking their language, and he even fancied himself as being one of them. He traveled extensively throughout the Arctic during the better part of the next decade, remaining away from European settlements and outposts for what he reported to be 18 months at a time. He wrote extensively about his experiences in a great number of books, as well as in the scientific literature of the period.[1]

Despite controversies surrounding his leadership failures on at least one major expedition and certain questionable matters concerning his personal life, Stefánsson was an undisputed authority on Arctic survival and the Inuit way of life. During his Arctic sojourns, he ate as the native people ate with no added food supplies. A repeated theme throughout his writing involved the observation of the Inuits’ supreme survival and hunting skills, frequently focusing on what and how they ate. He looked upon the Inuit people as a “superior race” by virtue of their extraordinary physical prowess and mental constitution, and he attributed much of this to their exclusively animal-source diet, which was most notably enormously rich in fat.

Most Arctic explorers of the day made a point of bringing their own food provisions on similar cold-weather expeditions and were careful to include abundant sources of citrus that could help offset the risk of scurvy in northern climes. As an anthropologist (having studied at the graduate school of Harvard University, where he also spent two years as an instructor), Stefánsson elected to apply some simple logic to this equation. He knew that the native peoples in this region had absolutely no scurvy and no nutritional deficiencies associated with their distinct lack of access to high-carbohydrate foods. He correctly surmised (and ultimately was able to prove to himself and others) that their diet must be inherently protective against the problems and concerns encountered or predicted by many of his peers. By challenging the status quo and embracing the indigenous Arctic lifestyle, Stefánsson became a highly controversial figure in his day. He also managed to attract some skepticism concerning his claims, as well as some notable scientific interest.[2]

Following widely publicized statements that he and his men had lived for extended periods of time in the Arctic on a diet of nothing but meat and fat to no apparent detriment, a group of scientists sought to investigate his claims. Stefánsson and one other man from his expedition, Karsten Anderson, agreed to an extraordinary experiment. Following the completion of Stefánsson’s field study and his preliminary reports, supplementary work would be conducted at the Russell Sage Institute of Pathology, a small research laboratory affiliated with Cornell University Medical College in Bellevue Hospital. At this time (1926), the general public was already being propagandized with the notion that eating meat (and, of course, animal fat) was harmful. It was widely believed that meat eating caused high blood pressure, kidney disease, hardening of the arteries, arthritis, and other health problems. Stefánsson’s claims fell under considerable attack, and he was eager and determined to secure impartial, reliable information. The plan was to find out exactly what would happen if two men in New York lived on nothing but meat and fat for a year (strictly supervised around the clock for dietary adherence). This study was reported in multiple peer-reviewed publications, the primary reports being published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry in 1930.[3,4] One interesting observation from the Bellevue study was that Stefánsson consumed a moderate amount of protein – roughly 15 to 20 percent of his estimated daily caloric intake[4] – while deriving an estimated 80 to 85 percent of his calories from fat. (This is a recipe for highly effective ketogenic adaptation, readily mimicking the considerable health and longevity benefits later observed with caloric restriction.[5])

Stefánsson was increasingly recognized as a world-class expert in Arctic native culture and diet, and he published an important book on the subject in 1946 with the title Not by Bread Alone. In 1956, an expanded version of the book was published under the title The Fat of the Land. In it, he expounded upon his many years of experience in the Far North from the perspective of diet and health, offering a historic and observational outlook on what he called “the home life of Stone Age man” and “living on the fat of the land.” It is an extraordinary and eye-opening read. During his extensive time in the Arctic, Stefánsson ate (by his own account) a diet that was calorically 80 percent comprised of animal fat, with the rest being mainly protein; all from the animals and fish he – and the Inuit he lived among – subsisted upon daily.

In his introductory comments in the book, he said, “If meat needs carbohydrate and other vegetable additives to make it wholesome, then the poor Eskimos were not eating healthfully the last few decades. They should have been in a wretched state along the north coast of Canada, particularly at Coronation Gulf, when I began to live among them in 1910 as the first white man most of them had ever seen. But, to the contrary, they seem to me the healthiest people I had ever lived with. To spread abroad the news of how healthy and happy they and I were on meat alone was a large part of the motive for writing this book.”

Later in the same commentary, he added, “And carbohydrates, as this book helps to explain, are not conducive to optimal health, at least not if taken as a high percentage of the meal. A distinguished orthodontist has said, in a passage we quote more at length thereafter, the Eskimos ‘are paying for civilization with their teeth’ [after the introduction of high-carbohydrate foods]. And, as this book means to show, the decay of teeth is only one of several important losses in health we suffer as a price of that food abundance which enables us to dwell in large cities and have ‘a high standard of living.’”[6(p xvi)] In a later paragraph, the same orthodontist was described and quoted in a more extensive fashion: Dr. Leuman M. Waugh from the School of Dental and Oral Medicine of Columbia University “whose heresies, like many of my own, were derived from seeing what the European way of life is doing to the Eskimos.”

As an aside, we now understand from the work of famed nutritional pioneer and researcher Weston A. Price, DDS, that dental health reflects meaningfully on health elsewhere in the body. Also, according to Richard Feinman, PhD, a biochemical researcher and professor of biochemistry at Downstate Medical Center (SUNY) in New York, “The deleterious effects of fat have been measured in the presence of high carbohydrate. A high fat diet in the presence of high carbohydrate is different than a high fat diet in the presence of low carbohydrate.”[7] In effect, it is metabolically akin to placing a lit fuse into a powder keg. Combining a love of fat with a love of sugary or starchy foods is effectively a recipe for disaster in the long term, as Stefánsson was to discover later in life. It is notable here that, unlike dietary fats and fat-soluble nutrients (as well as protein), literally no human dietary requirement for carbohydrates has ever been established by science. But protein/meat, on the other hand, is always meant to be consumed with an appreciable amount of fat for its most optimal metabolization and safe utilization.

In his writings, Stefánsson consistently pointed out that the Inuit made every effort to avoid consuming overly lean meat. They always kept the fattier portions for themselves while throwing any lean meat left over to their dogs.[8] In his now classic authoritative book about living and surviving in the Far North, Arctic Manual, Stefánsson wrote, “Fat is, in calories, the most condensed of foods. An ounce of fat (butter, bacon fat, tallow) is more than twice as nourishing in the caloric sense as an ounce of sugar or an ounce of dried lean [meat]. If portability of a ration is being considered, it is then essential that it shall contain as much fat as the consumer can take without beginning to turn against it; the rest of his requirements will be supplied from other sources. It is considered that the human body cannot repair itself without protein. Theoretically, then, the ideal condensed or portable ratio is as much fat as you need for calories and as much protein as you need for body repair.”[9(p224)]

This last sentence by Stefánsson is hugely important and is in alignment with the premise of my own Primalgenic® approach and its basic dietary recommendations – though my recommendations also include a lot more fibrous vegetables and greens than Stefánsson might have argued are necessary (for modern-day reasons I expand upon in my book Primal Fat Burner). And far from being a merely “theoretical” concept, it appears to be the recommendation most consistent with findings in human longevity studies and the best designed ketogenic research to date. Stefánsson, in short, was well ahead of his time.

He went on to describe in fascinating and pertinent detail many sources of fat (even within a single animal): “The great particular delicacies of the caribou eater are the various fats. Except perhaps some of the marrows, the best is that behind the eyes. There is also some very good fat under the lower jaw. When caribou are skinny the tongue is much fancied, for it usually contains some agreeable fat. Another good fat is around the kidneys. The least favored is the slab of fat which lies along the back.”

Illustrating the value of the bone marrow fat, he explained: “One thing dogs never get is the marrow bones. The meat is peeled from them, sometimes to be cooked, sometimes to be given to the dogs. The bones are then broken for marrow in the fashion of Stone Age man. The only marrow bones that are customarily boiled or roasted by Eskimos are the humerus and femur, which are cooked with a certain amount of meat still adhering. The rest of the marrow is eaten raw.”

He then said something extremely important: “Meat is a complete diet only when the animal you eat is fat.”[9(pp232-233)]

With respect to eating the meat of animals hunted during leaner times of the year, he wrote, “The only way to manage with beasts of seasonal fatness is to kill a large number at the top of the fat cycle and to preserve the fat.” Then he observed: “Some animals are never fat. The only one of these important in northern economy is the rabbit. It is recognized that you cannot live on them exclusively. The expression ‘rabbit starvation,’ common in the North, sounds as if you were talking about there being no rabbits. What the phrase means is that the people have been reduced to living on nothing but rabbit.

“If you are transferred suddenly from a diet normal in fat to one consisting wholly of rabbit you eat bigger and bigger meals for the first few days until at the end of about a week you are eating in pounds three or four times as much as you were at the beginning of the week. By that time you are showing both signs of starvation and of protein poisoning. You eat numerous meals; you feel hungry at the end of each; you are in discomfort through distention of the stomach with much food and you begin to feel a vague restlessness. Diarrhoea will start in from a week to 10 days and will not be relieved unless you secure fat. Death will result after several weeks.”[9(p234)]

Regarding the cooking of meat for maximum benefit, including protection against scurvy, the following passage offers an interesting insight: “The easiest method of cooking, and the one best liked in the long run, is boiling.… [They] find it best to boil meat about as rare as we cook roast beef. Our typical roast is well done only for a small fraction on the outside; inside there is a layer that is medium done, and innermost what we call rare, which is really raw. The eaters of boiled meat like the same to be the case, having the inside of each piece rare or medium. This practice has developed, no doubt, in response to taste or, shall we say, instinct. Scientifically speaking, oxidation destroys or weakens vitamin C in those outer layers of the meat which are well- or over-cooked. There is little oxidation on the middle layers and practically none on the raw (rare) central portion. Therefore, you are always protected from scurvy so long as your meat is cooked in approved Eskimo fashion.”[9(p236)]

Stefánsson had a unique appreciation for the central importance of fat in the diet – not only for Arctic and Native peoples the world over, but for everyone. Unfortunately, his wife’s love of preparing and serving him baked goods and pastries later in life (a temptation to which he clearly succumbed) led to an abandonment of his Inuit diet and eventually led – in all likelihood – to his sudden decline in health and his death by a stroke in 1962 at the age of 83. In the end, he regrettably failed to follow his own best advice.

A turning tide

Over the past several decades, fat has been greatly maligned, although the policies recommending low-fat diets have only moved their adherents farther from health.[10] At long last, however, the tide is turning and, at the very least, the grossly misguided vilification of this critical dietary factor is being called into question. Better nutrition books are finally being written. Ancestrally oriented (and even ketogenic) diets are in vogue. Public attitudes – if not official policies – are changing. But the recognition of dietary fat’s central importance to human health remains vague and as yet unrealized by most. My own book Primal Fat Burner was written to help settle that score. Fat – especially that of ruminant animals, poultry, etc., fed a diet of exclusively natural forage of uncompromising quality – is not just “not as bad as we once heard.” I am inclined to argue that the fat and fat-soluble nutrients of fully pastured animals are not only central to the optimization of human health but also literally central to what made us human in the first place. Furthermore, I make the case that a fat-based metabolism (rather than a glucocentric one) is the most natural and optimal metabolic state of humankind.

A primary metabolic reliance upon fat is unquestionably the most efficient metabolic state we can cultivate. It offers a broad range of long-term physiological and health-related benefits unmatched by any other dietary approach, increasing the natural efficiency of both the brain and the heart. According to scientific evidence, “A ketogenic state results in a substantial (39%) increase in cerebral blood flow, and appears to reduce cognitive dysfunction associated with systemic hypoglycemia in normal humans.”[11] Also, according to Richard Veech, MD, PhD, a longtime researcher and lab chief at the US National Institutes of Health, an effective state of ketogenic adaptation may demonstrably improve the heart’s functional efficiency by a whopping 28 percent![12] So much for the myth of dietary fat (in the absence of sugar/starch) adversely affecting heart health.

It’s important to point out here that dietary fat was not coveted by Arctic peoples alone, but by literally all ancient indigenous cultures – including those occupying hot climatic environments throughout the world. For example, Australian Aboriginal peoples were well known for their pronounced penchant for dietary fat. Emu meat (as well as that of the cassowary), which is particularly fat-rich, was highly sought out for this very reason. Dr. Carl Sofus Lumholtz, a Norwegian explorer who studied Aboriginals at the end of the 19th century, observed them eating mainly meat and fat, and almost no plant matter unless they had no other choice. He said they ate the best first and saved the rest for last – and “the best” was the fat![13] In one first-hand account of Aboriginal natives feasting upon an animal they had killed, Lumholtz wrote, “First the fat is taken and handed to greedy mouths; then the heart, liver and lungs; finally the body itself is to be divided…. But the greatest delicacy is the fat.”[14]

Stefánsson, in Arctic Manual, also commented on what he saw as an erroneous notion that dietary fat was more coveted by or important to those living in cold climates, stating, “Carl Lumholtz from Australia [reported] that natives there would gorge with fat.” He went on to say, “Insofar as man is a hunter he lives on fat animals in cold countries and animals comparatively deficient in fat in hot countries. Thus it is in hot countries we are likeliest to find people who are fat hungry. This is why fat animals, like the opossum and pig, are delicacies in tropical and sub-tropical lands.”[9(p222)] He pointed out that “the hottest countries are, in their lore and literature, the greatest praisers of fat.”[6(p xxii)]

Other anthropologists, such as Leon Abrams, Jr., MA, EDS, observed that when Aboriginal people killed a kangaroo, the hunters would immediately examine the carcass for its fat content. If it was deemed to be too lean, they would simply abandon it.[15,16] Anthropologists elsewhere recorded a similar hunting practice. In J.D. Speth’s excellent and scholarly book The Paleoanthropology and Archaeology of Big-Game Hunting, he quotes anthropologist N.B. Tindale as saying (of the Australian Aboriginal Pitjandjara people), “When [an animal is] killed they immediately feel the body for evidence of the presence of caul fat. If the animal is njika, fatless, it is usually left, unless they are themselves starving.”[17] Weston A. Price recorded his extensive observations concerning the impact of traditional diets on health in his now legendary scholarly work, Nutrition and Physical Degeneration. He found that, within those populations where mental and physical health was the most extraordinarily robust, the foods most consistently considered to be of the greatest sacred and dietary importance were invariably animal-source foods – particularly those richest in fat and fat-soluble nutrients.

Despite the enormous diversity of diets recorded by Price in his journeys, it was these two factors that were always the most consistent among the healthiest populations he studied. This key observation is often missed among many of Price’s fans in favor of the more commonly popularized “just eat real food” mantra. I would submit that Price’s identification of this core dietary commonality among wide ranges of cultural groups speaks to foundational elements that are basically true for all humans. After all, what defines us as a species is not our differences but those characteristics we share in common. The popular notion that “everybody is different” blatantly ignores human anatomy and physiology, and assumes that anything we are capable of consuming is optimal for us as long as it’s natural. Some people may tolerate certain post-agricultural foods better than others, but this should not be interpreted to mean that those foods are necessarily optimizing (or not somehow compromising) for their health.

Moreover, no living human possesses the fermentative digestive system of an herbivore. In fact, even herbivores, which are obligate consumers of 100 percent carbohydrate-based diets, obtain their primary caloric requirements from fat (and not carbs) – more specifically, shortchain saturated fats (butyric acid, mainly) from the bacterial fermentation of all the fiber they consume. In the end, it can be argued that all large mammals are designed to get much of their primary energy from fat. But, as humans, we are designed to consume the most fat by far, and only we humans – even as compared to other primates – have brains capable of running on almost nothing but ketones full time over the long term. In fact, all human infants are born in an effective state of ketosis, where ketones form the major fuel for brain development.[18] This is a unique and notably meaningful characteristic further distinguishing us from other mammals.

I certainly do not suggest that everyone should be consuming only meat and fat, but I do argue that animal-source foods of the highest quality, rich in fat and fat-soluble nutrients, form a universal foundation for optimal human health. This viewpoint is in alignment with our unique physiological/neurological makeup and with the enormous body of evidence gained from stable isotopic analysis of the human fossil record. I argue that anything added to this critical dietary foundation is basically nuance.

In the incomprehensibly toxic and stressful world we live in, it has become increasingly critical that whatever foods we add to this dietary foundation be enhancing of and not additionally compromising to human health. In my book, I make the case that fibrous vegetables and greens – rich as they are in beneficial phytonutrients, detoxifying effects, and additional fodder for our modern-day embattled microbiome – are a more important dietary inclusion for us today than at any other time during our long evolutionary journey.

In Primal Fat Burner, I make an extremely well-supported argument for dietary animal fat forming the most fundamental basis for our most unique human characteristic – our large and sophisticated brains. Human cognition is largely – and uniquely – predicated upon two very specific 20- and 22-carbon fatty acids: arachidonic acid (AA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), both of which are found in our food supply exclusively within animal-source foods of uncompromising quality. This is particularly important in regard to DHA. If DHA is not in your diet, it’s not in your brain in sufficient amounts for healthy cognition. It simply cannot be reliably synthesized from plant-based substrates by humans. In order to ensure adequate intake, I recommend meat, organs/tissues, and marrow from animals that were 100 percent grass-fed and grass finished. Cold water fish can certainly be another source of DHA, but the increasing contamination of our oceans and questionable quality of much modern seafood leads us to pastured meats as likely our best dietary option. Such meat also happens to be where many of our ancestors primarily got their DHA.

Animal fat forms the critical scaffolding for higher human cognition, while a fat-based metabolism adds to neurological, cognitive, and mood stability and helps protect us from toxins, inflammation, free radicals, and even ionizing radiation.[19] It is important to note that our brains are constructed from the fats with which we supply them through our food choices. I would adamantly submit that we must choose wisely in order to achieve a new and more rational state of consciousness, and a capacity to actually think, if we are to survive this modern age as a species.

Aldous Huxley once insightfully wrote, “Generalized intelligence and mental alertness are the most powerful enemies of dictatorship and at the same time the basic conditions of effective democracy.”[20] In an age where transnational corporate interests are actively subverting entire nations, and our minds, bodies, and very consciousness are being effectively molded and twisted by their power-hungry, greed-driven interests, we urgently need to wake up and take control of what we can. Diet and health (along with health freedom) are foundational to this equation. Without access to a healthy, unadulterated food supply and healthy, conscious dietary choices, we can have no health – and without that (and clarity of thought), we have nothing.

Albert Einstein once stated, with equal poignancy, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” Not to second-guess Albert, but I’d be inclined to tweak his remark to say, “We cannot solve the problems of the world with the same dysregulated brains we had when we created them.” We stand poised on the edge of our own oblivion as a species, and we lack the wiggle room (with respect to what it takes to have any semblance of health) enjoyed by our prehistoric ancestors, or even by those in Weston A. Price’s time. Living as we do in the most perilous and precarious period of our long evolutionary history, we have never needed more grounded, rational thought and greater awareness than we do now.

Thus, Stefánsson’s message concerning the central and foundational importance of dietary fat is more timely today than ever before. As the myths surrounding dietary fat and quality animal-source foods are finally being shattered by a voluminous body of independent science, this message underscores a foundational truth known for countless generations. It is also one that is key to our future survival as a species.

About the Author

Nora Gedgaudas is a board-certified nutritional consultant and clinical neurofeedback specialist with over 20 years of successful clinical experience. A recognized authority on ketogenic, ancestrally based nutrition, she is a popular speaker and educator and the author of several books, including the best-selling Primal Body, Primal Mind and Rethinking Fatigue. Her most recent book is Primal Fat Burner (Simon & Schuster, 2017). Nora’s accredited Primalgenic® health certification program, Primal Restoration®, is an invaluable source of unique, cutting-edge information benefitting those interested in furthering their nutritional knowledge and optimizing health. For more information, please see www.primalbody-primalmind.com and www.primalrestoration.com.

Price-Pottenger members can read hundreds of additional articles on our website.

To become a member, click here.

REFERENCES

- Mattila R. A Chronological Bibliography of the Published Works of Vilhjalmur Stefansson, 1879-1962. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Libraries; 1978.

- Stefansson V. Not by Bread Alone. New York: Macmillan; 1946. Introductions by EF DuBois, pp. ix-xiii; and E Hooton, pp. xv-xvi.

- McClellan WS, Rupp VR, Toscani V. Clinical calorimetry XLVI: Prolonged meat diets with a study of the metabolism of nitrogen, calcium, and phosphorus. J Biol Chem. 1930; 87:669-80.

- McClellan WS, DuBois EF. Clinical calorimetry XLV: Prolonged meat diets with a study of kidney function and ketosis. J Biol Chem. 1930; 87:651-68.

- Veech RL, Bradshaw PC, Clarke K, et al. Ketone bodies mimic the life span extending properties of caloric restriction. IUBMB Life Journal. April 3, 2017.

- Stefansson V. The Fat of the Land. New York: Macmillan; 1956.

- Volek JS, Feinman RD. Carbohydrate restriction improves the features of metabolic syndrome. Nutrition & Metabolism. 2005; 2:31.

- Stefansson V. The Friendly Arctic. New York: Macmillan; 1921.

- Stefansson V. Arctic Manual. New York: Macmillan; 1944.

- Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs of the United States Senate. Dietary goals for the United States. 2nd ed. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1977.

- Hasselbalch SG, Madsen PL, Hageman LP, et al. Changes in cerebral blood flow and carbohydrate metabolism during acute hyperketonemia. Am J Physiol. 1996; 270:E746-51.

- Taubes G. What if it’s all been a big, fat lie? New York Times Magazine. July 7, 2002.

- Brayshaw H. Well Beaten Paths: Aborigines of the Herbert/Burdekin District, North Queensland; An Ethnographic and Archaeological Study. Townsville, Qld: James Cook University; 1990.

- Lumholtz C. Among Cannibals: An Account of Four Years’ Travels in Australia and of Camp Life with the Aborigines of Queensland. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons; 1889:297.

- Abrams HL. The preference for animal protein and fat: A cross-cultural survey. In: Harris M, Ross EB (eds.). Food and Evolution: Toward a Theory of Human Food Habits. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University, Press; 1987:207-23.

- Hayden B. Subsistence and Ecological Adaptations of Modern Hunter/Gatherers. New York: Columbia University Press; 1981.

- Tindale NB. The Pitjandjara. In: Bicchieri MG (ed.). Hunters and Gatherers Today. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1972:248.

- Medina JM, Tabernero A. Lactate utilization by brain cells and its role in CNS development. J Neurosci Res. 2005; 79:2-10.

- Curtis W, Kemper M, Miller A, et al. Mitigation of damage from reactive oxygen species and ionizing radiation by ketone body esters. In: Masino SA (ed.). Ketogenic Diet and Metabolic Therapies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Huxley A. Moksha: Aldous Huxley’s Classic Writings on Psychedelics and the Visionary Experience. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press; 1999:187.

Published in the Price-Pottenger Journal of Health & Healing

Spring 2018 | Volume 42, Number 1

Copyright © 2018 Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation, Inc.®

All Rights Reserved Worldwide