Access to all articles, new health classes, discounts in our store, and more!

Toxins in the Kitchen – The Hidden Dangers of High-Oxalate Foods: An Interview with Sally K. Norton, MPH

Our executive director, Steven Schindler, first met nutritionist and researcher Sally K. Norton at the Ancestral Health Symposium held in August 2021 at UCLA. This fortuitous meeting led to two recent, in-depth conversations about the dangers of dietary oxalate, a little known subject on which Sally is a leading expert. These sessions have been edited down into a single interview format providing vital information on the importance and practice of oxalate-aware eating.

● ● ●

Steven Schindler: What are oxalates and why should they be avoided or minimized?

Sally Norton: Oxalates are chemical toxins that hide within many of our most popular foods, even ones that we consider “superfoods.” They are invisible culprits behind a wide range of contemporary health problems. Because many of these foods are so deeply trusted, almost no one is making the connection between their consumption and our most common maladies, including digestive issues, aches and pains, low energy, poor sleep, and worse problems. Oxalate-aware eating is critically important today, and to understand why, some knowledge of the science surrounding them is needed.

Although there are people who have never heard the term, oxalate is a very ubiquitous family of chemicals. Its parent compound is oxalic acid, a naturally occurring corrosive acid that is highly reactive. Oxalic acid is a chelator of metals, and it bonds with minerals including calcium and iron. As it interacts with these minerals, it can precipitate out to form crystals. In scientific terminology, when oxalic acid has minerals attached to it, it is called an oxalate. But, in popular usage, the crystals, together with oxalate salts and oxalic acid, are collectively known as oxalates.

Oxalic acid is made by plants – which use it for various purposes, including defending themselves against being eaten by predators – as well as by fungi and bacteria. It is even formed in clouds and can be a component in acid rain. In addition, some oxalate is naturally produced in the human body as a metabolic waste product. Metabolic oxalate is usually made at a rate and quantity that the body is equipped to excrete, but our consumption of oxalates in plant-based foods, even at moderate levels, can lead to a condition of overload.

When we consume a high-oxalate food, such as a kiwi, we are actually eating both oxalic acid and calcium oxalate crystals. That can cause a lot of oxidative stress and cellular damage. Tiny oxalate crystals can attach to our cell membranes and cellular debris, particularly at sites where there are inflamed, infected, dying, or regenerating cells. If the cells are unable to dissolve and discard an attached crystal, the crystal will attract more oxalate particles and grow. Because we tend to eat oxalate all the time, we suffer acute stress following high oxalate meals and create a buildup in our bodies. This combination of daily stress and a toxic backlog contributes to many disease processes.

Steven Schindler: Would you tell us more about how oxalate affects the body and what plants we commonly find it in?

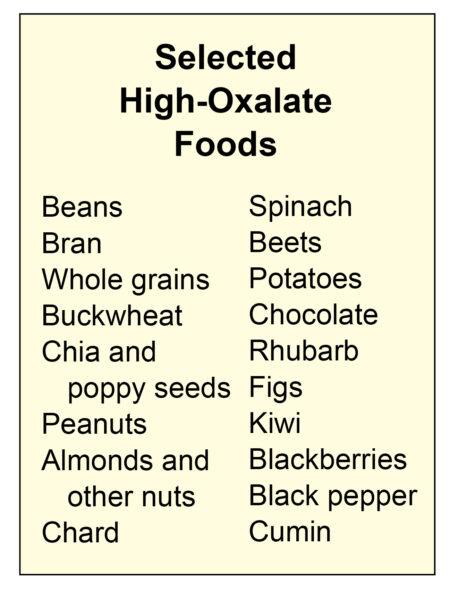

Sally Norton: Although most plants produce oxalate, not all of them make it at the same rate. Some contain so much oxalate that they are considered inedible. Rhubarb is a classic example of a high-oxalate plant that we use as food. If you grew up around rhubarb, you were taught not to eat the leaves because they are quite poisonous. It’s oxalic acid and oxalate crystals that make them toxic. But we don’t stop to think how much of the rhubarb stalk we should be eating or whether it’s okay for children to consume it. In actuality, children can get sick not just from the leaves, but from the “edible” stalk itself. While rhubarb is typically not a staple used routinely, many other foods with a high oxalate content are extremely popular. Such day-to-day high-oxalate foods include potatoes, peanuts, almonds, chocolate, spinach, chard, beets, bran, buckwheat, and beans.

The most frequently recognized type of oxalate toxicity is the kidney stone. Eighty percent of all kidney stones consist primarily of calcium oxalate, which forms when oxalate accumulates in the kidneys and starts grabbing calcium. Often, doctors blame the calcium and talk about “calcium stones,” but that’s really a misunderstanding that lets oxalate off the hook. Moreover, kidney stones are not the most common manifestation of oxalate toxicity. Although they are a growing problem, impacting increasingly younger people and more and more females, they are said to affect “only” 12 to 15% of the population.

There are numerous more common problems associated with too much oxalate in the diet. These develop because oxalate doesn’t just form crystals in the kidneys and urine; it also interferes fundamentally with the functioning of any cell exposed to it. Oxalate damages the mitochondria (the power plant of the cell), causes oxidative stress, and shortens the cell’s life span. Its effects on your body can initially be subtle because you have trillions of cells. But, ultimately, the buildup of oxalate can start eroding the integrity of connective tissues and the function of glands and blood vessels.

Oxalic acid is absorbed from our food into the bloodstream, which carries it straight to the liver and then on to the heart and the lungs. It’s toxic to blood cells, including circulating immune cells. It travels through the vascular system to the kidneys, which filter it out and concentrate it (increasing the chances of it crystalizing), and then the acid and crystals travel to the bladder, where they can cause irritation. People who wake frequently at night to urinate may have bladder irritation from too much dietary oxalate. That can develop into a chronic condition called interstitial cystitis, which can be life altering because you might need a bathroom every 15 minutes and have trouble holding urine. Oxalate is quite toxic to the nerves and muscles, including the sphincters that allow for proper elimination and swallowing.

Initially, a high-oxalate diet can result in less obvious symptoms, such as generalized malaise, poor concentration, joint stiffness or swelling, and muscle pain or weakness. But, over time, it can cause a wide variety of health problems, including kidney and intestinal damage, breathing disorders, gum and tooth issues, bone and connective tissue instability, arthritis, autoinflammation, cataract formation, and vascular disorders. Because oxalate is a neurotoxin, it affects brain function in ways that can bring on anxiety, depression, and dementia.

High oxalate intake also promotes mineral deficiencies, especially of calcium and magnesium. Oxalate ions bind these minerals, blocking us from accessing them in our food and stealing them from our cells, body fluids, and bones. In addition to depriving us of essential minerals, oxalate overload creates extra demands for vitamins B6 and B1, contributing to functional deficiencies of those nutrients.

Steven Schindler: Is there evidence of oxalate overload in ancestral communities? And what is it about our modern diet that causes high oxalate consumption?

Sally Norton: I know of one set of studies, cited in a research article published in 1998, that talks about the severe abnormal tooth loss found among some desert-dwelling hunter-gatherers from the Archaic period. In the lower Pecos region of west Texas where their skulls were found, prickly pear cactus and agave – which are very high in calcium oxalate crystals – were dietary staples for 6,000 years. These people lost all their molars by age 25, and by age 40, they were completely toothless. We often talk about how the dentition in ancestral remains is quite lovely, but this was not the case in these people who were eating high-oxalate plants. Their remaining teeth had evidence of dental microwear, and the research article concluded that calcium oxalate crystals from their diet, which are harder than tooth enamel, had worn them down.

One thing missing from that conclusion, however, is the recognition that the teeth are not only damaged by abrasion from chewing the crystals. The blood flow to the teeth and jaw carries oxalic acid to the area. In addition, the salivary glands concentrate oxalate to 10 to 30 times the amount in the bloodstream. That means the teeth are bathed in oxalic acid after a high-oxalate meal, and it can contribute to issues such as dental tartar, gum inflammation, and the erosion of our oral health.

In our modern diet, the impact of dietary oxalate is compounded by the constant availability of high-oxalate foods. We no longer eat seasonally, as our ancestors did. We have access to foods such as potatoes, peanuts, and spinach year-round, which was never the case in ancestral communities. We also eat high-oxalate foods in forms that ancestral populations never had, such as spinach smoothies and almond milk. So in our high-tech food era, we are in much bigger trouble than previous generations were from oxalate overload, which is contributing to all the major chronic diseases of our time. The lack of seasonality helps to keep oxalate damage unrecognized yet progressive.

All disease comes from deficiency and toxicity. I have mentioned that oxalates can cause nutrient deficiencies. But they also provide a great example of how we can become toxic from foods made by nature, not just the commodity products of industry. We’ve been so focused on how industrialized foods are malnourishing us, and so taken with the belief that plant-based diets are healthful, that we’re overlooking the fact that some plants naturally contain poisons deserving our attention and respect.

Steven Schindler: Is there a way to measure how much we are being affected by oxalate overload?

Sally Norton: If it were easy to measure oxalate overload, the answer to that question would already be in the lexicon of healthcare and commonly known. In fact, that’s a principal reason why we’re oblivious to oxalate toxicity. There’s really no good way to quantify the extent to which oxalates are affecting your cells and how much is accumulating in your body.

In clinical settings, the early signs of oxalate overload illness are recognized only in retrospect, if at all. Doctors don’t suspect oxalate overload, don’t know what tests might be called for, and don’t understand the limitations of the available tests. Until about 30 years ago, accurate measurement of blood and urine oxalate was a major technical problem. Now, even though we can measure oxalate levels more accurately, urine and blood tests still tell us little about how much oxalate resides in our bodies. They cannot tell us whether we are sick from oxalate overload or how sick we might be. Also, measures of blood and urine oxalate don’t necessarily correlate with symptoms, for a variety of reasons. For one thing, symptoms don’t neatly correspond to recent oxalate intake, but instead may flare up as the body releases oxalate during times of lower consumption.

We love our health metrics nowadays, and we think they are very scientific. A lot of people even carry a metric device on their wrist. But tests and metrics aren’t a good way to determine if oxalates are harming you. It’s better to gradually transition into a moderate (150 mg per day) then to a low-oxalate diet (50 mg per day) and carefully monitor your symptoms. The diet can offer some strong indicators, when it is implemented correctly and consistently.

Of course, this requires accurate data on the oxalate content of foods, and that can be difficult to obtain. One reason is that the oxalate content of any given food varies from sample to sample and test to test. But beyond that, the unreliability of some published data is a common source of error and confusion. You can find more accurate estimates of the oxalate content of common high-oxalate foods (and, in some cases, lower-oxalate counterparts), based on data from reputable labs, in the Resources section of my book, Toxic Superfoods.

Kidney researchers tell us that a safe intake level falls within the range of 150 to 200 mg per day. High-oxalate eating is typically defined as 250 mg or more per day, while diets containing over 600 mg per day are considered extremely high. It’s easy for people who are trying to eat a healthy diet to consume extremely high levels of oxalate, when a single spinach smoothie can contain around 1,000 mg.

Steven Schindler: What is the best way for us to reduce our oxalate intake?

Sally Norton: It’s really not that hard to begin a low-oxalate diet. You don’t have to eliminate oxalate completely, in the way that you would need to avoid gluten if you had celiac disease. What’s important is to not exceed your body’s threshold for toxicity. One of the major factors determining that threshold is how much the kidneys can get rid of effectively. I believe that people striving for good health are eating four to five times that amount.

Once you have identified the worst offenders in your diet, you can start by eliminating the one that you like the least. Gradually replace the high-oxalate foods in your diet with lower-oxalate alternatives. Go slowly to avoid destabilizing the oxalate deposits in your body and flooding your tissues; and be consistent.

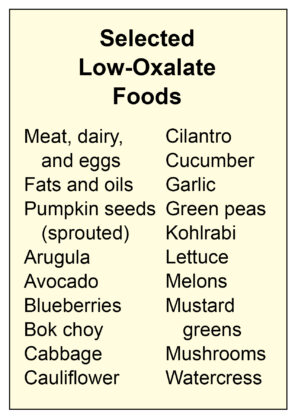

Replacing high-oxalate foods with low-oxalate substitutes is easy. Low-oxalate foods include all the lettuces and almost all the greens, except the three bad guys – chard, beet greens, and spinach. Sorrel is a fourth one that hardly anyone uses in this country. In the fruit department, kiwi, starfruit, pomegranate, and blackberries are among the highest in oxalates. There are other fruits you can enjoy instead. For example, the cucurbit family is very low in oxalate. That would be all the melons, including watermelon, cantaloupe, and honeydew. Winter squashes and cucumber are cucurbits as well.

High-oxalate grains include both whole grains and the pseudo-grains buckwheat, quinoa, and teff. You can replace these with foods such as white rice or pearl barley. However, a lot of people in the ancestral space ask: Why bother with grains at all? I think that’s a reasonable question, as you don’t actually need grains in a healthy diet.

Once you’ve changed your diet to control oxalate exposure, there are a number of things you can do to support your recovery from overload. Lemon juice or another source of citrate can help support kidney function and facilitate the removal of crystals from your tissues. To use fresh lemons therapeutically, consume at least two per day – in hot lemonade, for example – and sip some plain water afterward, to protect your teeth from the effects of the acid. Mineral supplementation can also be extremely helpful. You need calcium to bind the oxalate in your gut and facilitate its excretion in the feces. Magnesium is needed to bind oxalate, restore enzyme function, and support bowel function and urinary excretion of oxalate.

Often, a person with oxalate issues will experience a temporary worsening of some symptoms after being on a truly low-oxalate diet for a while. This could be a sign that your cells are moving stored oxalate out and undergoing damage in the process. Sticking with the diet is an important part of getting through this healing process. It’s also important to stay with the diet during those times you are feeling better, to avoid exacerbating the root cause of your symptoms.

Steven Schindler: Are there factors that might make some people more susceptible to harm from oxalates?

Sally Norton: Yes, though some of these factors are not quite characterized as well as we would like. As individuals, we have epigenetic or genetic differences that can affect the processing of chemicals and potentially increase our oxalate load. These differences may affect your ability to transport oxalate or may cause your body to hold onto it in ways that hide what is going on. For example, the immune system can wrap oxalate crystals in dead white blood cells or extruded DNA, effectively keeping their effects invisible to you for a long time. Meanwhile, they might be making your bones more brittle or your tendons stiff, or they might start damaging your vision. You won’t necessarily feel bad in the short term; you might not have the inflammation, pain, fatigue, and sleep problems that can occur when oxalate is actively affecting your nerves and muscles. However, you will be building up a toxic debt that will eventually come due.

Another factor is your absorption level. How much oxalate you put in your mouth isn’t the same thing as how much enters your bloodstream. While a lot of the oxalate you eat stays in your digestive system, a certain percentage passes from the intestines into the blood, and that’s called the absorption rate. According to current estimates, our normal absorption rate is between 10 and 15% – but your absorption rate can be as high as 70%, especially if you have a health condition such as leaky gut.

In leaky gut, the spaces between the cells of the digestive tract are too wide, and excess fluid flows between the cells, carrying oxalate with it. If you have leaky gut, your absorption level will be high, and you won’t need a high-oxalate diet to make yourself sick from oxalate overload. People who have undergone bariatric surgery have chronic leaky gut and intestinal inflammation, so they can easily be overexposed to oxalate.

Your ability to move oxalate quickly out of your body is another major factor. If you have sluggish kidneys, you’re not going to get rid of it as well, and you will accumulate higher levels in your blood. Then the rest of your body will have to grab it and hold onto it, to get it out of the bloodstream. You can’t leave oxalic acid in the bloodstream at high levels because it disturbs electrolytes, which interferes with the heart’s pacemaker function. That can lead to arrhythmias or even heart block, which is a kind of electrical heart failure.

If you have chronic inflammation from any cause, including obesity, insulin resistance, or diabetes, you are at increased susceptibility to high absorption, poor excretion, and elevated levels of endogenous production in the liver. Note that the liver creates oxalate, it doesn’t detoxify it, and the amount it creates is influenced by our daily intake of precursors, such as vitamin C. In fact, taking more than 250 mg of vitamin C a day will increase the oxalate in your body quite a bit. The use of collagen can also raise your oxalate load, as its amino acids are potentially significant oxalate precursors.

Other factors that increase your likelihood of oxalate overload and associated symptoms include a diet low in calcium and other minerals (dairy-free and vegan diets are two examples), and the frequent consumption of gut-irritating foods, such as beans, bran, whole grains, and quinoa. The repeated use of antibiotic or antifungal medications and long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory pain medications (NSAIDs) can also make you more vulnerable to oxalate accumulation and damage.

If you have a degenerative disorder, chances are your blood and tissues will be greatly overexposed to oxalate even on a fairly conservative diet. In fact, if you have any kind of metabolic weakness or are frail in any way, oxalate overload will probably impact your health much more seriously and quickly. Eventually, too much starfruit or too many spinach smoothies could even be fatal for a person who’s really frail.

Steven Schindler: Why don’t we hear more about oxalate and its potential to cause disease?

Sally Norton: I talk about this in Toxic Superfoods early on, because people are shocked to learn that many plants that we think are so fabulous are actually harmful. Why don’t we know this? I used to w onder that, too. I was angry that, as a person with a nutrition degree from a great school, working in public health, I didn’t know this. Our ignorance stems from that fact that it’s not in our textbooks and it’s not a topic of discussion.

In addition, the oxalate research that has been conducted focuses exclusively on kidney stones. Oxalate does show up as a factor in cell biology and rheumatology studies because it causes problems, and there have even been some studies demonstrating that it induces breast cancer, yet these things haven’t been pursued. Mostly, researchers just use oxalate as a reagent in lab vials. When we test blood for glucose, oxalate is one of the preservatives used because it destroys the cell’s ability to use the glucose. This suggests that it interferes with our metabolism and probably contributes to blood sugar dysregulation. However, that is not in any of our textbooks because a lot of the basic science hasn’t been completed.

Since the 1970s, the literature has shown over and over again what I think is conclusive evidence that eating a high-oxalate diet is the major driver of kidney stones. It’s the same with chronic kidney disease. The major toxin that creates chronic kidney disease is oxalic acid from foods. Yet the scientific community has not admitted that, partly due to issues around funding future research.

Nowadays, what seems to get people’s attention is what can we solve with a product. Research is funded based on fads and interest levels, and things like oxalate are never going to be that popular. Telling people to eat less almonds and spinach so they won’t get kidney stones just isn’t sexy in today’s world. And I’m sad to say that my colleagues in integrative medicine and nutrition show very little interest in this topic.

There are actually a lot of reasons why we don’t hear more about oxalate. As far back as the 1930s, we knew that eating spinach could deplete the body of calcium and retard children’s growth. The AMA Council on Foods and Nutrition refrained from mentioning that because of the beta-carotene and other nutrients in spinach. There’s been a certain denial of the value of such information for over a hundred years, and the situation hasn’t gotten any better because we believe that plants are always benevolent and benign, when in fact that’s not really the case.

Steven Schindler: Would you tell us about your personal experience with oxalates?

Sally Norton: I love natural foods, and gardening and cooking at home, and I thought I knew how to eat in a healthful way. I followed the prevailing health advice, cutting salt, gluten, and sugar out of my diet, and limiting red meat and fats. For 16 years, I was a vegetarian or vegan, and after giving that up, I continued to embrace plant-based whole foods. Yet, beyond their connection with kidney stones, I was oblivious to the inherent problems of regularly eating high-oxalate foods. I never suspected that they could be the cause of my life-long health problems.

Starting at the age of 12, I suffered through three decades of health challenges. Over the years, I had chronic foot, joint, muscle, and back pain; sinus infections; irritable bowel syndrome; thyroid issues; reproductive problems; and a debilitating sleep disorder. At age 35, I added sweet potatoes to my diet as a daily staple to replace wheat and beans, to which I had become intolerant. Very quickly, I started developing age spots on my skin and wrinkles around my eyes, and getting stabbing muscle pains in my upper back, but I didn’t see any connection with the sweet potatoes. My symptoms continued to worsen, and by age 46, I was so mentally and physically fatigued, and my back pain was so out of control, that I had to leave my career as a health researcher and grant writer.

It wasn’t until three years later that I started to recognize that oxalates and arthritis pain could be connected. I began to consistently avoid my go-to high-oxalate foods – mainly, sweet potatoes and chard – and multiple personal miracles began to unfold. The sleep disorder vanished, decades of pain and joint problems receded, and I started to feel younger. Within months, my feet finally worked properly after 30 years of problems, and my ability to read, function, and do research was restored, eventually enabling me to write my book.

Steven Schindler: What led you to write Toxic Superfoods?

Sally Norton: Throughout my career, I basically avoided telling people how to live. I stayed in academia and designed, wrote, and supervised grants for research. I led an integrative medicine project to bring alternative and complementary therapies into the curriculum of conventional healthcare providers in medicine, dentistry, nursing, public health, and pharmacy. I was hiding out in academia because I never wanted to be in a food argument or tell people what to eat. So, it was a heavy lift for me to start working one-on-one with people and getting into the food advice business.

I guess the real thing that made me want to write this book and bring its message forward is that I had followed all the dietary rules in my efforts to be healthy, and I paid a dear price for it. They were wrong, and I was wrong. I was going on false notions and what amounts to a huge sin of omission by my own profession of public health nutrition. And there are many people in the same situation who are struggling with their health and don’t have access to the information and resources they need.

Mostly, what we’ve achieved in my profession is a worldwide epidemic of obesity, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses. There has been an explosion of autoimmune conditions and all of these new, complex problems that involve immune system dysregulation and the breakdown of various systems of the body. Often, by the time we reach what should be our golden years, we’re hobbling off to a lot of doctor appointments.

I know we’re not meant to age like that. People who are trying to get healthy deserve to have a lot more energy, health, and well-being than I ever got to have. So I decided that I would be a tiny lighthouse at this edge of the sea, warning people: “Don’t hit these shoals! Don’t do what I did!” It’s been an interesting trip, finding out how many people really need this information. It’s gone way beyond anything I imagined.

Steven Schindler: How does your book dispel the myth that eating plants will make us all happy and healthy?

Sally Norton: One entire chapter looks at the dangerous trends and myths around plants. It discusses how our present-day dietary fashions and plant-centric food culture keep us from recognizing the nutritional shortcomings and toxicity of high-oxalate foods. Various popular diet movements – such as the gluten-free, keto, and paleo movements – are really pushing foods such as spinach and nuts. They are leading us into an increasingly toxic way of eating, and we’re not willing to see it.

We’ve also bought into the mistaken idea that phytonutrients are doing something great for us. Around the 1980s, people started talking about phytonutrients as antioxidants, when in fact they are pro-oxidant toxins that stimulate healing responses from the body as a defensive mechanism. We get antioxidant responses from cells in petri dishes, but that is not how the body actually works. In the digestive process, our body’s machinery is trying to protect us from absorbing these phytochemicals, and then to quickly disarm them with liver and digestive enzymes. In Toxic Superfoods, I discuss a handful of studies that demonstrate when you remove these supposed antioxidant compounds from the diet, the oxidative stress of the body goes down. The evidence is that the body is much happier without them.

I share that in the book because I want people to be okay with the idea that you don’t have to eat chard and spinach. Avoiding them won’t put you in a nursing home or make you sick. Rather, these foods can cause illness and make you feel old before your time. In fact, there isn’t a strong argument to keep eating any high-oxalate foods.

When you eliminate high-oxalate foods from your diet, you may find that the way your body responds will be dramatic. This is very real to those of us who have lived it. Many people have found relief from – or even reversed – a wide range of conditions and syndromes, simply by swapping their high-oxalate foods for low-oxalate alternatives. In the long term, oxalate-aware eating can potentially prevent injury, arthritis, and osteoporosis, and can slow age-related degeneration. Undertaken correctly, it can dramatically improve your health and quality of life.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Sally K. Norton, MPH, is a nutritionist with a unique specialty: warning us that healthy eating can get us into trouble. Sally earned her nutrition degree from Cornell University and a master’s degree in Public Health from UNC-Chapel Hill. Her prior career included health professions education in the principles and practices of integrative medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and public health research design and administration at Virginia Commonwealth University. She is the author of the book Toxic Superfoods (December 2022). Sharing her own experience and knowledge of oxalates has helped many people improve their health and recover from serious illnesses, chronic pain, kidney problems, osteopenia, and even chronic infections just by making simple changes to their diet. You can find Sally and learn more at sallyknorton.com or on Instagram @toxicsuperfoods_oxalate_book.

Steven Schindler is the executive director of Price-Pottenger. A nonprofit strategist and business management expert, Steven is leading a community-informed evolution of Price-Pottenger’s mission to advance the organization’s impact on public health.

Published in the Journal of Health and Healing™

Winter 2022 – 23 | Volume 46, Number 4

Copyright © 2022 Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation, Inc.®

All Rights Reserved Worldwide