Access to all articles, new health classes, discounts in our store, and more!

Supporting Healthy Methylation: An Interview with Kara Fitzgerald, ND

PPNF: What is methylation, and why is it important to us? A lot of people have heard about it, but it appears that very few understand exactly what it is.

Kara Fitzgerald: It’s hard to get a sound bite that explains methylation, and I think that’s because it’s so incredibly fundamental and far-reaching. It’s happening in every cell of the body all the time. A methyl group is one of the smallest, most fundamental functional groups found in our molecules. It’s simply a carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms. Methyl groups play incredibly important roles in many bodily systems, including those of detoxification, neurotransmitter production, and epigenetic regulation of gene expression.

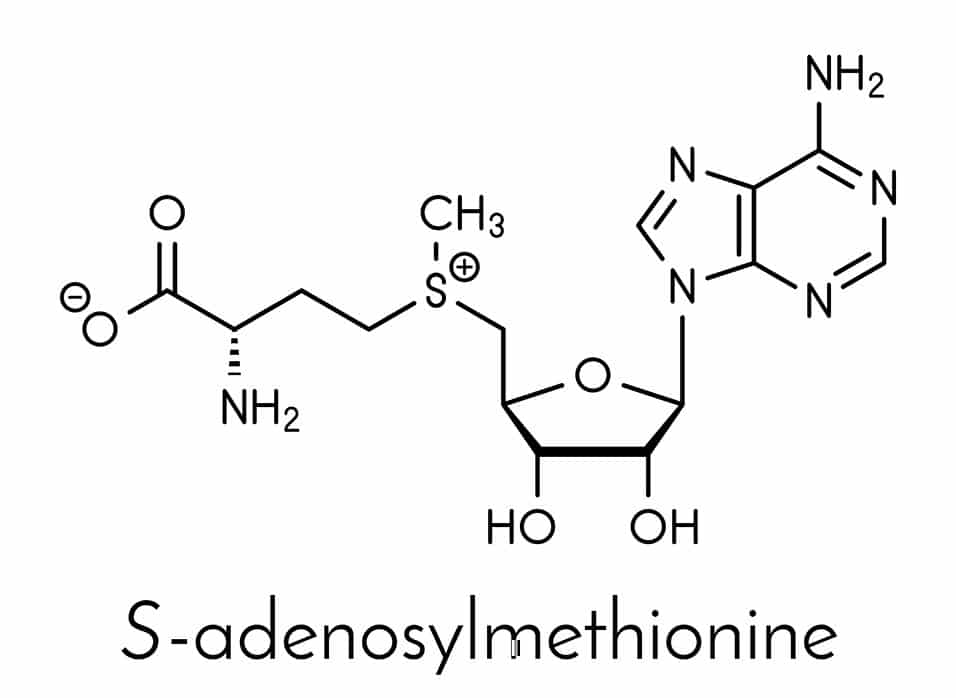

We have a methylation cycle, which basically puts a methyl group onto a molecule called S-adenosylmethionine – often called either SAMe or SAM for short. Because that methyl group can then readily be donated to other molecules, we refer to SAMe as the universal methyl donor. SAMe can activate or deactivate different molecules throughout the body by putting methyl groups onto them.

For example, we convert the neurotransmitter noradrenaline to adrenaline, our fight-or-flight hormone, by putting a methyl group on it. Then, interestingly enough, we metabolize adrenaline with a second addition of a methyl group, although there are a few other steps involved in that. So, we activate adrenaline with a methyl group, and then we turn it off by adding a methyl group – and our universal methyl donor, SAMe, is involved in both of those reactions.

A host of nutrients, including vitamin B12 and folate, are involved in the methylation cycle. That’s one reason many people today are interested in taking these vitamins. They’re trying to support the production of SAMe so that methylation happens unimpeded.

PPNF: What are the typical symptoms or health conditions associated with impaired methylation?

KF: I know that people really try to nail that down, listing these as symptoms of hypo- or undermethylation, and those as symptoms of hyper- or too much methylation. But because it’s such a fundamental process, pointing to a specific list of symptoms does not, I think, quite appreciate the level of complexity and the ubiquitous nature of methylation. However, we can point to a handful of conditions in which methylation clearly plays a major role.

Autism is one of these. The research is pretty clear that individuals on the autism spectrum have difficulty making SAMe or that other parts of the methylation cycle are subfunctional. The methylation cycle is intimately associated with another cycle – we call it the transsulfuration cycle – that makes extremely important compounds such as glutathione, the main antioxidant in our bodies. If methylation is dysregulated, sulfuration is often going to be problematic, too, and you might see things like insufficient glutathione and higher oxidative stress. Routinely, individuals on the autism spectrum have problems in that area.

Depression has also been linked to methylation problems. There’s been a reasonable amount of research looking at the link between them, and there have been some good outcomes in treating depression with higher doses of folates. I would say that methylation problems can be a piece of the puzzle in depression, but not every depressed individual is going to respond to folate.

Neural tube defects are, in part, an issue of compromised methylation, and we’ve seen the powerful impact of folic acid fortification in reducing their incidence. The public health initiative in the Western world, especially in the United States, of fortifying grains with folic acid has certainly been a topic of disagreement. However, it was a very successful public health campaign in that it made sure people had enough folic acid, and it reduced considerably the incidence of neural tube defects.

Those are just three areas in which methylation plays a role. Defects in methylation are also associated with many other conditions, including ADD/ADHD, allergies, diabetes, chronic fatigue, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Not everybody is going to have significant methylation deficits that are causing their clinical symptoms. But when we start to think about genetic methylation, also called DNA methylation, the question really becomes: What isn’t potentially related to an imbalance?

Aging is a hypomethylation process. As we age, if we’re not tending to ourselves well, we will see a trend towards less effective methylation. In elderly populations, homocysteine routinely rises, and that increase is associated with a lower DNA methylation pattern. So, one of the things we focus on in anti-aging and longevity medicine is supporting healthy methylation.

PPNF: How do the typical American diet and lifestyle contribute to methylation problems?

KF: Most people following a Western diet are not consuming the optimal breadth and amount of the myriad methyl donor nutrients involved in the production of SAMe. They might be getting some folic acid from eating processed grains, but there are a symphony of nutrients involved in healthy methylation. We need to not only take in sufficient nutrients but also reduce the things that can be damaging to methylation, such as sugar or alcohol, which can profoundly impact the methylation cycle.

It’s been very clearly demonstrated that many toxins – metallotoxins, such as mercury and lead; organotoxins, such as BPA; and xenohormones – can damage DNA methylation. Not only can high exposure to environmental toxins place excessive demand on methyl donors, but toxins may also impact DNA methylation via other mechanisms, including endocrine disruption, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

Medications can have a pretty big impact on methylation through a variety of routes, not the least of which is the burden of detoxifying some of the medication. Some drugs impair nutrient absorption, some inhibit enzyme function, and others deplete SAMe. For example, antacids and proton pump inhibitors can increase the risk of B12 insufficiency, and oral contraceptives increase folate requirements.

Stress will also tax methylation at many levels. When we’re in a constant fight-or-flight state, where we’re producing loads of adrenaline, we need healthy methylation in order to be able to metabolize and eliminate that adrenaline. Both posttraumatic stress and increased life stress alter DNA methylation. Also, there are many interesting studies finding evidence that in utero exposure to maternal stress alters offspring stress responses.

Exercise has an impact on methylation, either helping or hindering it depending on how you exercise and if you’re doing it in a way that’s balanced for the body. When done regularly and at moderate intensity, exercise can be an effective antidote to factors that can deplete methyl donor reserves or negatively alter methylation activity, namely psychological stress, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

Sleep also has a profound impact. Poor sleep hygiene can contribute to oxidative stress and consequently tax methylation pathways.

PPNF: Would you talk about the role of the gut microbiome in methylation?

KF: The gut microbiome is a major player in both metabolic and genetic methylation. For one thing, a healthy microbiome is going to make a lot of those methyl donor nutrients that we’ve been talking about – folate, B12, and so forth. In addition, a lot of the compounds made by a healthy gut microbiome can go on to regulate genetic expression in very important ways, such as through the production of butyrate by certain gut bacteria in the presence of adequate fiber. Our microbiome activates a lot of the polyphenols we obtain from various plant foods into compounds that help regulate DNA methylation. The various compounds produced by our microbiome will either support healthy genetic methylation or hinder it.

Specific bacterial species may exert different effects on DNA methylation. Dysregulation or overgrowth of gut bacteria can hinder nutrient absorption, with consequences for effective methylation. Moreover, unfavorable microbial balance may underlie local and systemic inflammation, potentially impacting methylation activity.

PPNF: If we work to improve our methylation patterns, can we pass those changes down to our descendants?

KF: Yes. We know that the methylation patterns on DNA can be passed down. Biologist Randy Jirtle and his colleague Rob Waterland showed that to be true in the famous agouti mouse studies, where feeding mice nutrients such as vitamin B12 and folic acid before and during pregnancy affected DNA methylation and gene expression in the offspring.

There was also a famous event, called the Dutch Hunger Winter, in which Germany blocked delivery of food supplies to the occupied western part of the Netherlands during the winter of 1944-1945, and the people were put into starvation mode. Women who were pregnant during that time gave birth to offspring with altered DNA methylation patterns that resulted in increased risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity. Moreover, those changed genetic methylation patterns were passed down through multiple generations.

This is very important to consider during preconception, for both women and men. We want to optimize health as much as possible so that we can pass on good epigenetic patterns to our offspring.

PPNF: Increasingly, we hear about healthcare practitioners prescribing high-dose, long-term supplementation with methylation factors, such as B12 and folate, to avoid or correct methylation deficits. Are there any problems with that?

KF: In clinical practice, there is definitely a time and a place for supplementing with vitamins that support methylation. If somebody has a B12-associated or folate-associated anemia, they absolutely need robust supplementation. However, we want to have an endpoint in mind with that kind of supplementation. We don’t want to leave them on those nutrients for life. Because genetic methylation is very complex, there is reason for us to pause in prescribing high-dose methyl donors, especially for the long term, and ask ourselves if we could be causing harm.

The “shotgun” approach of using supplements to correct methylation problems is not uniformly successful. Not everyone responds well, and some people even find they cannot tolerate supplementation, despite a clear need for methylation support. In some of these individuals, a worsening of symptoms and the appearance of neurological issues may result. Also, there is now research that suggests the need for caution when using long-term, high-dose supplementation of methylation factors, as conditions such as autoimmune disease, autism spectrum disorder, and cancer have associations with excessive methylation.

When you look at the genes of any individual, you can see regions of hyper- and hypomethylation, both of which can affect disease processes. Cancer is a good example because a lot of research has been done on methylation, gene expression, and cancer. We see that tumors are able to hypermethylate and turn off tumor – suppressor genes. Likewise, they can use hypomethylation to activate tumor-promoting genes. This type of scenario can be seen in many other chronic conditions, as well.

Even in older people, who tend to have less robust methylation, you can see regions of hypermethylation on individual genes, and those regions can be associated with increased prevalence of chronic diseases. We need to support healthy methylation, but we don’t want to push it so far that we encourage hypermethylation of areas of the gene where it isn’t wanted.

In short, regulation of the epigenome – the complement of chemical compounds that modify gene expression – is a highly complex process, and we cannot state with certainty what the impact is of high-dose, long-term methylation interventions. Thus, for the vast majority of our patients, we need to consider whether such supplementation really is the right approach. Rather than forcing methylation forward, perhaps our ultimate goal should be to enable the body to do the right thing at the right time.

PPNF: Do you feel that the amounts of methylation nutrients such as folic acid that are found in most popular multivitamins could be hazardous for certain groups of people?

KF: The bulk of the research seems to support the use of a multivitamin with sufficient folate and other associated nutrients in pregnancy. The vast majority of it seems to demonstrate that healthy offspring result with these nutrients. However, regular folic acid supplementation and fortification are now strongly suspected to carry risks – despite their clear benefits in preventing neural tube defects – especially at levels above the recommended daily intake of 400 mcg of dietary folate equivalent units. Populations who regularly consume fortified foods such as ready-to-eat cereals and fortified grains can have a folic acid exposure up to the tolerable upper limit of 1.0 mg per day, and with the use of multivitamin supplements, it is not uncommon for intake to rise beyond that. It does seem that high intake of folic acid is associated with a modest but statistically significant increased risk of certain cancers in some individuals.

For a long time, people in my field said, well, that’s because folic acid is synthetic. That might be a piece of the puzzle, but we know that natural folates can alter genetic methylation in a way similar to folic acid. It seems reasonable that ingesting relatively high amounts of exogenous nutrients involved in methylation could be problematic for some, especially over the long term. Research into this area is needed and will likely be forthcoming.

PPNF: Would you say that methylated B vitamins, such as methyl folate and methylcobalamin, are better for us than their non-methylated counterparts?

There are some individuals with a relatively rare condition called cerebral folate deficiency who should not take folic acid. As the name implies, they don’t have enough folate in their central nervous system – and it does look like folic acid can hinder the transport of the natural folates into the central nervous system. For that population, folic acid would be toxic, but they’re a minority.

Arguably, the natural or bioidentical forms of these vitamins are probably a little better than the others. A recent study suggested that when you take methylcobalamin, your body has to break the methyl group off the cobalamin and then repackage it. So, methylcobalamin is probably not better than any other form of B12. It’s just a lot more expensive. As a clinician, I’m going to lean on the side of something that’s bioidentical to the form used in the body, especially if it’s readily accessible. However, I don’t think we necessarily have to avoid the other forms.

PPNF: Would you explain what a MTHFR polymorphism is and whether it necessitates the use of nutritional supplementation to boost methylation?

KF: MTHFR stands for methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, an enzyme that converts folate into the active form (5-MTHF) that can be used to make SAMe. This enzyme also helps to keep homocysteine within normal levels. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) or variation in the MTHFR gene may impair the functionality of the enzyme.

MTHFR is an extremely common mutation, and you don’t necessarily need to supplement if you have it. You might want to get evaluated to see whether there is evidence of a need for B vitamins or other nutrients involved in methylation. The presence of a MTHFR mutation, regardless of whether it’s homozygous or heterozygous isn’t necessarily a life sentence requiring you to supplement forever.

There are many genes involved in the methylation cycle. To point our finger at just one is really bad science, and research doesn’t support it very strongly. A lot of us are in the habit of looking at MTHFR, myself included, but I’m casting a wider net and not leaning heavily on it.

SNPs are, by definition, extremely common, and we wouldn’t survive as a species if they were all that significant, would we? So, we have to be balanced in how we think about them. My thinking, and that of the team I work with – particularly my friend and colleague, Romilly Hodges, with whom I authored the book Methylation Diet and Lifestyle – is that eventually we’ll find multiple patterns of SNPs that influence health much more significantly than a single mutation. We’re going to need “big data” to help us really sort through our gene patterns and determine which ones are strongly influencing us – and we don’t have that technology available to us yet.

You can go to 23andMe or other direct-to-consumer companies to get some of your SNPs identified. There are all sorts of websites that will interpret that data, and often they will tell you that you need to take a lot of supplements. People come to my practice who have gone that route and are very overwhelmed. They come in with a couple of shopping bags’ worth of supplements that they’ve been taking for a long time, and it’s really pretty heartbreaking to me because I think the significance of those, by and large, has been overstated.

Epigenetics is a science that’s new and evolving, and most of the studies are still being done on cell cultures or animals. The research on humans is fairly limited. I think it can be empowering to offer genetic evaluations directly to consumers, but, right now, we really don’t know what to do with all that information. Consumers go online and start doing searches, and they can become overwhelmed and scared that they’re going to be subjected to certain diseases because of their genes. There’s a massive amount of misinformation.

PPNF: In your book, you recommend supporting methylation with nutrients from food. Would you explain why?

KF: Food-based nutrients seem to be a safer way to support methylation activity, especially over the long term. To date, there’s no research that implicates food-based methyl donor nutrients in increasing disease risk. In fact, when we consume greens and all the other beautiful foods that support healthy methylation, our disease risk decreases.

Because aberrant genetic hyper- and hypo-methylation are associated with various diseases and accelerated aging, we want to provide the body with the necessary ingredients from a good whole-foods diet and allow it to make the decisions around how, when, and where to methylate. In other words, by removing the obstacles to and drains on methylation while providing broad-spectrum nutrient ingredients for balanced activity, we are allowing physiological wisdom to manage the process.

We evolved eating a diet rich in methyl donor nutrients, and the methylation cycle is reliant on many of these, including various B vitamins—we’ve talked about folate and B12—as well as minerals such as magnesium and zinc, amino acids such as methionine, and all sorts of other actors. Choline from eggs is a major player. We want a diet rich in all those nutrients.

For example, we can get folate from foods such as liver, legumes, sunflower seeds, and leafy greens. Animal products, including seafood and meats, especially liver, provide vitamin B12. Nuts, seeds, cocoa, whole grains, and legumes are some of the foods rich in magnesium, while shellfish, pumpkin seeds, and sesame seeds are among the good sources of zinc.

When we return to the elegance and nutritional complexity of a healthy diet and just allow the body’s wisdom to determine how the nutrients are going to be used, we can’t go wrong. Then, if we need to occasionally use nutrient supplementation to provide additional support, that’s okay, in my opinion.

Thus far, we’ve talked about foods that are rich in the various methyl donor nutrients. Now, I want to talk about another class of nutrients that aren’t involved directly in the methylation cycle. These are nutrients we’re calling methylation adaptogens. They are, primarily, polyphenol compounds that appear to be able to modulate DNA methylation patterns. They’re not directly pushing methylation forward; instead, they seem to be balancing it.

Some of our favorite superfoods from many different traditions contain compounds that can balance methylation and affect gene expression, and our Methylation Diet is extremely rich in such foods. Methylation adaptogens include resveratrol, found in grapes; quercetin, in onions and many other plants; rosmarinic acid, in rosemary; epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) in green tea; curcumin, in turmeric; and some of the polyphenols in one of my favorite foods on the planet, blueberries. In addition, there is equol, a compound found in foods such as flaxseeds; and lycopene, in tomatoes. Vitamins E, D, and A, and zinc also appear to have methylation-balancing properties. Any good diet focused on optimizing gene expression should be loaded up with these fabulous compounds – and it’s not difficult to do.

We provide some recipes and sample menus in Methylation Diet and Lifestyle, and we have also produced a cookbook – Everyday MDL – that includes even more recipes that we have designed to support healthy methylation. [See a sampling of recipes from Methylation Diet and Lifestyle on pages 29-31, this issue.] In addition, you can check out the recipes on our website and see some of our favorite dishes there. Those that are rich in our methylation superfoods are marked with an “approved” stamp on the site.

PPNF: Would you discuss some of the basic principles of the Methylation Diet?

KF: A Methylation Diet food plan should be nutritionally rich, anti-inflammatory, low-glycemic, high in antioxidants, and supportive of detoxification processes. A balanced diet based on whole foods – vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, seeds, complete proteins, and whole grains – will provide plentiful methylation nutrients.

Methylation superfoods, including beets, spinach, sea vegetables, daikon radish, shiitake mushrooms, salmon, fish roe, whitefish, oysters, eggs, and pumpkin, sesame, and sunflower seeds, contain high levels of methylation-specific nutrients. Organ meats such as liver are also valuable sources of relevant nutrients, especially the vitamins B2, B3, B6, and folate, as well as choline and betaine.

Here are a few basic guidelines. Include varied, colorful plant foods in your diet, and make sure you have a high fiber intake, which feeds the healthy bacteria in your microbiome. Eat organic as much as possible, and emphasize “low and slow” cooking methods and raw foods. Stay properly hydrated.

There are many reasons to have a rich, varied complement of fats in your diet. It’s beneficial to produce a little bit of ketones, the byproducts of fatty acid metabolism, as these are anti-inflammatory and favorable to healthy methylation. We advocate medium-chain triglycerides, as found commonly in coconut oil or in ghee, which also has some butyrate in it. We also recommend olive oil and the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids found in high-fat fish, such as salmon. DHA, an omega-3 found in these fish, is directly involved in regulating methylation.

Your food plan should also limit or avoid factors that negatively impact methylation. Because we want the diet to be low glycemic, minimize simple carbohydrates and added sugars. High blood sugar is not a friend to methylation. Reduce or eliminate fortified grains, especially if folic acid supplementation is not tolerated. Also minimize consumption of alcohol, which produces unfavorable DNA methylation patterns, impedes folate metabolism, and may interfere with SAMe activity.

Avoid foods known to contain significant amounts of toxins, such as meat and dairy products from animals given antibiotics or hormones, and high-mercury fish, including tuna, king mackerel, shark, and swordfish. When cooking animal products, avoid high-heat methods, such as grilling and deep frying. Don’t use plastic food and beverage containers.

Caloric excess can hinder proper methylation, so refrain from overindulgence. You might even consider intermittent fasting, which is beneficial to metabolic and genetic methylation. We routinely recommend intermittent fasting when prescribing our more intensive program.

Of course, in addition to diet, our program takes into consideration many aspects of the lifestyle. There’s much you can do to help yourself. You can get the proper amount of sleep, and if you have sleep apnea, correct it. Make sure you’re getting enough exercise, but don’t push yourself beyond capacity. Do the best you can to modulate stress, and, to the best of your ability, limit exposure to environmental toxins. All of those things are going to impact methylation, particularly at the level of gene expression. We get into details in the book.

KF: There’s a continuum of how you can embrace the program. You can choose to simply incorporate the principles into your daily regimen, as we often do in our clinic. All of our patients are introduced to MDL foods as a part of their treatment program. However, we often prescribe a grain-, legume-, and dairy-free, lower carbohydrate/ketogenic-leaning MDL program (called the MDL Intensive) when needed for a more aggressive strategy. Further, we find that the principles of MDL may readily be layered into any other therapeutic nutrition plan. For example, MDL works well on a standard elimination diet (removing any antigenic MDL foods) or a FODMAP-restricted or specific carbohydrate diet.

The MDL Intensive would be particularly helpful for an individual who needs folate and B12 but can’t tolerate supplementation or for someone who has elevated homocysteine. It’s also a good diet for anybody who’s very interested in anti-aging or has any of the myriad conditions that have been associated with imbalanced methylation. It supports detoxification, stress reduction, and microbiome and hormone balance. You could even consider using it as a detox protocol that you employ on a quarterly basis. Many of us go on detox diets at the seasonal changes of the year, and using the MDL Intensive program would be perfect for that. Then, during the rest of the year, you could just layer the ideas into your regular diet. I think that the MDL program is appropriate for most conditions and that it can be tailored to meet individual needs.

PPNF: In closing, is there anything else you would like to tell our readers?

KF: Ryan Bradley, ND, and I are doing a controlled epigenetic study right now, testing this protocol in a small cohort of individuals. We’re evaluating the effects of a nine-week diet and lifestyle intervention on patient-reported quality of life, symptoms, and methylation-related biomarkers in men between the ages of 50 and 72. We’re measuring DNA methylation using the Illumina EPIC array as well as the standard methylation biomarkers, such as homocysteine and S-adenosylmethionine. We are also looking at different folate vitamers, lipids, and fasting glucose. So, we’re researching the principles being discussed here, which is very exciting to me. There’s no other research study actively going on, to my knowledge, that is looking at methylation and gene expression by tracking diet, exercise, meditation, and sleep.

In our study, we are providing very specific and intentionally designed dietary guidelines. We’re also using a probiotic that we hope will help to increase folate in the gut and to maintain a healthy gut microbiome. In addition, we’re using a polyphenol-rich powder, like a greens food powder, in our protocol. So, we’re promoting balanced methylation through diet, the lifestyle factors we talked about, and the use of a probiotic and a greens concentrate.

I’ve mentioned that aging is a process by which genetic methylation changes. UCLA professor Steve Horvath has created an epigenetic clock so he can look at methylation sites on DNA and actually determine the rate of biological aging. One of the questions in our research study is: Will this diet and lifestyle program that we’re recommending have a favorable influence on the epigenetic clock? We’re certainly hoping for that.

About Kara Fitzgerald

Published in the Price-Pottenger Journal of Health & Healing

Summer 2018 | Volume 42, Number 2

Copyright © 2018 Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation, Inc.®

All Rights Reserved Worldwide