Access to all articles, new health classes, discounts in our store, and more!

Raising Heritage Turkeys on a Family Farm: An Interview with Dave Heafner and Leslie Pesic

Dave Heafner and Leslie Pesic are the owners and operators of Da-Le Ranch, a small working farm in Lake Elsinore, California, specializing in farm-fresh meat, including meat from heritage breeds. Their products include beef, lamb, pork, rabbit, and the eggs and meat from chickens, turkeys, and various game birds. They practice sustainable farming methods, and sell their products at farmers’ markets, as well as through a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program.

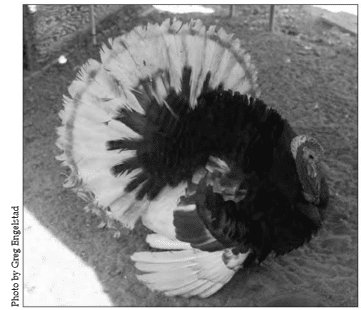

A few weeks ago, Dave and Leslie took time out of their busy schedule to give PPNF president Ed Bennett and board member Greg Engelstad an interview and a tour of their ranch. We were particularly interested in learning more about heritage turkeys, which are attracting growing consumer interest.

PPNF: How did you get started with the ranch?

Dave: We were living in San Diego, California. I had a business far removed from farming – I had been a Marine for 20 years and then a financial services provider for about the same length of time. Leslie had a degree in theology and worked for a church as an administrative assistant, and she had found a hobby that she really enjoyed – raising purebred dogs. Then I got ill, and lost my business because I was unable to work. I was sick in bed for a couple of years and was told I would die. I wanted to move out of the city and find a house where Leslie would be able to live and have her dog business.

We looked for property out of town, the only caveat being that if we moved to a rural area, I was going to raise meat for myself – and she would have to at least taste a bite of meat from every type of animal I raised. Since she was a vegetarian, that took a bit of convincing. After we moved, the first thing I did was buy a small flock of chickens, some rabbits, and six pigs. When the first pig was ready, I slaughtered it and grilled pork chops out back. I put that first bite of pork in her mouth, and a metamorphosis took place. She said, “I didn’t know meat could taste like this.” We’d both grown up eating the cheapest cuts of commercial meat available, and that’s what she had thought meat tasted like. After tasting that pork chop, however, she started eating a lot of meat. We hadn’t planned to be farmers when we moved up here, but we ended up adding more and more animals to our inventory. Leslie’s animal care instincts took over, and she became the heart of the farm. She loves animals – they’re all her babies, and they love her.

We first began selling our meat here at the ranch. Our only advertising was our listings on the Local Harvest website and Craigslist. At that time, we sold only whole animals, halves, and quarters, because the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits selling red meat by the individual cut unless it has been inspected under the Federal Meat Inspection Act. Today, our meats are inspected at USDA facilities, when required. In 2008, we were asked to sell our meat at farmers’ markets in San Diego and Bonsall, and we now participate in over a dozen in San Diego, Riverside, and Orange counties.

PPNF: What do you do here that is different in the way your animals are raised? Raising Heritage Turkeys on a Family Farm

Dave: Because of the current drought, we have no grass and limited water. To have mills add grass to a feed mix would be very expensive. Instead, we mix our own feed, which is grass based. It takes more work than buying ready-mixed feed, but a better result is achieved. We also use fodder – hydroponically grown sprouts, most often barley. We mix the sprouted fodder with our proprietary feed ingredients to offer our animals healthy and balanced meals, without hormones, steroids, subtherapeutic antibiotics, GMOs, or soy.

We’re convinced that the drought is going to persist long term, so we bought a fodder system that we will soon be putting into full operation. The apparatus consists of 15-foot-long trays in which you sprout the seeds. In seven days, when the barley reaches its highest protein content, you cut the mat of sprouts into little chunks and throw it out to your animals, just like you would do with alfalfa. We give fodder to all our animals, except the sheep, who just want alfalfa.

Leslie: We feel the animals in our care should be protected, nurtured, and raised humanely. That includes providing them with clean food and water, and protection from predators. Because I mix my own feed for our animals, I know exactly what they are getting. I also put garlic in their water and in their food. It’s a natural antibiotic, antiparasitic, wormer, and immune system builder. All animals can benefit from its use. We use DE (diatomaceous earth) as well, to get rid of various parasites.

PPNF: Since Thanksgiving is coming up, let’s talk about heritage turkeys. How would you define a heritage breed?

Dave: It’s a variety of turkey that has been around a long time and is more closely related to wild turkeys – the original turkeys in this country – than are the commercial strains. It’s capable of breeding on its own, so it doesn’t have to be artificially inseminated like the commercial birds. Heritage turkeys do better outdoors in a somewhat rugged environment. They are more capable of dealing with the elements than commercial turkeys, and they will roost in trees, whereas a commercial bird won’t. A young penned turkey may go up on a roost, but by the time it’s 12 weeks old, it may be too heavy to sit on one. Commercial birds have been crossed and recrossed to get a bigger breast, and they get so heavy that they can’t breed naturally. Heritage turkeys are also generally less susceptible to some diseases, particularly those diseases that have been around for a long time.

PPNF: When did interest in preserving heritage breeds come about?

Dave: In the late 20th century, some people in the industry started noticing that our heritage breeds, the standard breeds of the day, were starting to disappear. By the 1960s, heritage turkeys had been driven from the market by the industrial Broad-Breasted White, and by 1990, they were very close to extinction. A group of organizations including the Livestock Conservancy, the Society for the Preservation of Poultry Antiquities, and the Heritage Turkey Foundation launched efforts to restore breeding populations of these birds, and Slow Food USA has supported this movement. There are now approximately 25,000 heritage turkeys grown each year in the U.S., compared to 200 million industrial turkeys.

PPNF: How many different breeds would that represent?

Dave: There’s only one basic breed of domestic turkey, as the different varieties are all related. The heritage varieties include the Bourbon Red, Royal Palm, Standard Bronze, Beltsville Small White, White Holland, Narragansett, Slate, Midget White, and Black Spanish. We raise Bourbon Red and Standard Bronze birds.

Due to the relative scarcity of heritage birds, we’ve had a harder time getting chicks each year. We haven’t yet hatched our own turkey eggs but plan on testing this in 2015. The turkeys you see here are shipped to us from a hatchery, and are three days old when we get them. Heritage turkeys are ready to sell at about 24 weeks old, and are fully matured by 28 weeks. In contrast, commercial birds are ready for market at around 16 weeks.

PPNF: It appears that, due to the expense of raising these breeds, heritage turkeys sell for a higher price. Why would a consumer be willing to pay more for one of these?

Dave: From an altruistic standpoint, they might want to promote the continuance of the heritage breeds. From a “pocketbook” point of view, they don’t mind spending more for better-quality food. Finally, from a taste perspective, everyone we sell to says these are the best turkeys they have ever eaten.

PPNF: How does a consumer know if they’re getting a real heritage turkey?

Dave: That can be difficult because a store might put a high sticker price on a turkey that’s not a heritage breed. However, there are some things you can check for, starting with the price. If you get a free turkey with a $50 grocery purchase, you’re not getting a heritage turkey. If it’s 99¢ a pound, you know it’s not heritage. Even at $4 or $5 a pound, it’s probably not. Most of the farms with which we are in contact sell heritage birds for around $9 to $12 per pound.

Also, if it’s got a really enlarged breast, it’s a commercial turkey. I’ve seen some Broad Breasted turkeys with a breast as big as all the dark meat combined. When you look at the commercial turkeys in the stores, you will see that they’re all oval shaped. The breast and wings are very big, and the legs are very small. If it’s a heritage turkey, the weight should be more balanced. The breast may be half again as big as the legs, but if it’s radically larger, be suspicious. Our Standard Bronze birds can have a pretty good-sized breast – maybe four to six pounds – but on the commercial birds, the breast can weigh twelve pounds or more.

PPNF: Is there a difference in the fat content of a heritage turkey compared to a commercial one?

Dave: There can be a lot of difference if the turkey is primarily corn- or soy-fed in a commercial operation – that bird will probably have a lot more fat on it. If you fed a heritage bird that way, locked it in a pen, and didn’t let it run around, it would get fat, too. It’s really hard for a consumer to know for sure whether it’s a heritage bird unless they know where it was grown. This relates back to why farmers’ markets are so popular now. Most people who sell at farmers’ markets are growing their own stuff or having it grown for them.

PPNF: One advantage to shopping at farmers’ markets is that, in many cases, the consumer can talk to the farmer directly.

Dave: In our case, you can even come to the farm and “meet your meat before you eat.” I make a joke out of that, but it’s really one of our mottos. We also plan to start raising individual birds for specific customers. After the first of the year, we’re going to have a program that we’re trademarking as “Friend of the Farm.” By that time, we expect to be hatching our own turkey eggs. When you join this program in January, you can put your deposit down on a turkey. We’ll raise that turkey for you for Thanksgiving, and you’ll be able to come up to the farm once to visit it, and even participate in its preparation, if you desire.

We’re also developing a “chicken lease” program, where we will lease hens for you to keep in your backyard for egg laying. A part of the program would allow us to raise them here for you if you didn’t want to take them home. Your birds would then produce a certain number of eggs each year for your family. More information on the ranch can be found at www.da-le-ranch.com and www.facebook.com/Da.Le.Ranch.Meat.

Price-Pottenger members can read hundreds of additional articles on our website.

To become a member, click here.

Published in the Price-Pottenger Journal of Health & Healing

Fall 2014 Volume 38 Number 3

Copyright © 2014 Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation, Inc.®

All Rights Reserved Worldwide