Access to all articles, new health classes, discounts in our store, and more!

Is Macular Degeneration Preventable – and Treatable – with Diet?

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), an eye disease that leads to vision impairment, is known to affect legendary actress Dame Judi Dench, age 82, and famed novelist, Stephen King, age 69. Both have spoken publicly of their eye conditions. Dench says that she has trouble reading her lines for movies, while King reports no vision loss as yet. Dench and King are not outliers. They are just two of the millions of people with this potentially devastating disease, which gradually steals the central vision.

AMD is the leading cause of irreversible vision loss in people over the age of 65 in developed nations.[1] By 1994, some 15 million Americans over the age of 50 were estimated to be affected by AMD.[2(p1266)] Globally, some 196 million people are expected to be afflicted with the disease by the year 2020, with that number projected to rise to 288 million by 2040.[3] For people between 45 and 85 years of age, this translates to 8.69 percent with some degree of AMD.[3] In 1992, in the United States, nearly one in three adults over the age of 75 was determined to have AMD.[4] Even worse, as of 2002, the World Health Organization determined that 8.7 percent of the world’s blindness and severe vision loss, affecting some 14 million people, was secondary to AMD.[5]

Orthodox ophthalmology has found many associations with AMD, but its underlying cause has remained elusive. As written in the 1994 edition of Albert & Jakobiec’s Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology, which serves as a major reference for ophthalmologists, “Since the cause or causes of AMD are unknown, we lack the means for its prevention.”[2(p1273)] This statement remains true for orthodox ophthalmology today. For decades, AMD has primarily been associated with aging (hence, the name “age-related macular degeneration”) and, more recently, genetics. Although increased AMD prevalence has also been associated with heart disease,[6] type 2 diabetes,[7] obesity,[8] and metabolic syndrome,[9] there generally has not been any suggestion that these conditions are the cause of AMD.

In August 2016, at the Ancestral Health Symposium, I proffered the following hypothesis for the first time publicly: The displacing foods of modern commerce are the primary and proximate cause of AMD. To those who are familiar with Weston A. Price, DDS, whom many nutrition researchers consider the “Father of Nutrition,” the term “displacing foods of modern commerce” will be quite familiar. This term equates essentially to refined white flour, refined sugars, most vegetable oils (primarily, polyunsaturated oils), and trans fats – in short, man-made, processed foods.

I first developed this hypothesis in late 2013, and nearly three years of investigative journalism, interviews, and research have culminated in the authoring of a book on the subject. That book, Ancestral Dietary Strategy to Prevent and Treat Macular Degeneration, was originally published in September 2016.

Why diet – not aging or genetics – as the cause of AMD?

In late 2013, it occurred to me that, if macular degeneration was all about aging and genetics, as orthodox ophthalmology asserts, the prevalence of the disease should have been the same a century ago as it is today. We generally believe that our DNA, the master architectural plan of our bodies, is stable over very long periods of time, even thousands of years. In fact, our DNA is generally believed to be immutable. Evolutionary biologist and Paleolithic nutrition pioneer S. Boyd Eaton, MD, wrote, “Our genetic makeup, especially that regarding our core metabolic and physiologic characteristics, has changed very little between the emergence of agriculture, roughly 10,000 years ago, and the present.”[10]

Given that fundamental concept, I asked myself two questions: First, was AMD always as prevalent as it is today? And second, when could ophthalmologists even see the retina? The latter question arose because, obviously, ophthalmologists would have to visualize the retina in order to diagnose or even characterize macular degeneration. If the evidence favored AMD as being an unusual or rare disorder in the past and ophthalmologists were collectively able to visualize the macula during that time period, that would strongly point to an environmental factor at work. The suspected environmental factor – as we now know is the case with most chronic metabolic diseases of modern civilization, such as heart disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, cancer, and obesity – is “Westernization” of the diet.[11]

The history of AMD in the U.S.

It may come as a surprise to the lay public, but we physicians have virtually no education about the history of medicine, even within our own specialty. In fact, as far back as 1896, just before the American Academy of Ophthalmology was founded, German physician Rudolph Virchow said, “It is one of the worst aspects of our present developmental stage of medicine that the historical knowledge of things diminishes with each generation of students. Even independent young researchers can normally be assumed to have a historical knowledge of no more than three to five years at a maximum. Anything published more than five years ago does not exist.”[12(pxvi)]

Virchow’s statement remains true today. In medical school, my internship, and my entire three-year ophthalmology residency, I learned virtually nothing about the history of medicine or the history of ophthalmology. In fact, when I began to research the history of macular degeneration, the single most common retinal condition of our time, I was stunned to discover that I couldn’t find a single resource in which this had already been documented. That led me on a search that would take months to complete, digging up antiquated textbooks from the 1800s as well as scientific papers published in the late 1th century and beyond, with the assistance of reference librarians from around the world. These relics from medical history held astonishing facts that not only were germane to my hypothesis but also turned out to support it.

So back to the question: When could ophthalmologists first visualize the retina? The answer: in 1851, because of the genius of German-born physician and physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, who not only invented the ophthalmoscope but published the design so that it could be reproduced by manufacturers.[12(p76)] The ophthalmoscope became the first device that eye care providers would use to visualize the optic nerve, macula, blood vessels, and the rest of the retina. Within a decade, this technology had spread around the world. It also resulted in a number of retinal atlases being produced during the 1850s and 1860s.[12(pp191,195-196)]

Curiously, however, despite the fact that these atlas images virtually always included the macula, as it is in the center of the view through the ophthalmoscope, none of them ever depicted anything resembling AMD. In fact, 23 years would pass after Helmholtz’s publication of the ophthalmoscope design before the first cases of macular degeneration were characterized. In 1874, English ophthalmologist Jonathan Hutchinson described four cases that he had collected from his practice.[13] After another 11 years of silence on the subject, German ophthalmologist Otto Haab discussed the equivalent of macular degeneration in a lecture in 1885.[14] Yet another decade later, Haab published a paper in which he had evaluated some 50,000 ophthalmic patient medical records. From these, he determined that macular degeneration was as rare as myopic maculopathy and traumatic maculopathy – two conditions that are very rarely detected in the retina.[15,16] For perspective, in 24 years of ophthalmology practice, I have witnessed less than a handful of these two conditions combined, yet I have typically seen that many patients with AMD in any half day of practice.

The literature remained almost silent on the condition of macular degeneration until about 1930, despite the fact that the optic nerve and retinal conditions were the subject of great discovery, numerous papers, and many book chapters. In case one is left to wonder about widespread use of the ophthalmoscope, ophthalmologists Edmund Landolt and Herman Snellen had collected some 86 versions of the instrument by 1880, 140 versions by 1901 (on the 50th anniversary of the Helmholtz design), and 200 models by 1913.[17]

In 1927, English ophthalmologist Sir Stewart Duke-Elder published his first comprehensive textbook of ophthalmology. The eminent Duke-Elder, who would become the most dominant force in ophthalmology for more than four decades, was not only revered but prolific. His 1927 textbook was 340 pages in length, yet failed to even mention macular degeneration, an omission that was typical for textbooks of that era.[18] Thirteen years later, however, in Duke-Elder’s next comprehensive textbook of ophthalmology, he dedicated some thirteen pages to the condition, including seventeen images, six of which were in full color. He referred to macular degeneration as “a common cause of failure in central vision in old people.”[19] Obviously, by the 1930s, macular degeneration had risen from the status of medical rarity to a somewhat more common condition. Duke-Elder, however, did not mention any known or suspected degree of prevalence.

By 1975, the first ever large-scale, epidemiologic study of the prevalence of AMD was completed, and this was the Framingham Eye Study.[20] In this study, in order to meet diagnostic criteria for AMD, subjects had to have vision loss to 20/30 or worse and to have drusen, the yellow-white metabolic deposits in the macula that are characteristic of the disease. In the Framingham study, 8.8 percent of the subjects between 52 and 85 years of age were determined to have AMD, with 27.9 percent of those between 75 and 85 meeting the definition of the disease.

This historical review and recent research indicate that AMD was a medical rarity between 1851 and 1930, and subsequently rose to epidemic proportions in the US by 1975. Perhaps even more concerning, most developed nations have followed suit, developing high degrees of both incidence and prevalence of AMD in recent decades. The question is: Why?

The displacing foods of modern commerce – a historical view

Until 1880, it was nearly impossible to consume a nutrient-deficient diet, assuming one had enough food and a sufficient variety of food. History is very clear that all of the chronic metabolic diseases – i.e., Western diseases, such as heart disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, and obesity – which are so prevalent today, were medical rarities at the turn of the 20th century.[21] Without question, there have always been some people whose nutrition has been poor, sometimes despite a near abundance of nutritious, natural food being available. This has likely been the result of poverty, poor food choices, war, confinement, drought, or conditions such as alcoholism.

In 1880, however, for the first time, refined white wheat flour was produced on a large scale, because that was the year that roller mill technology replaced stone mill technology for grinding wheat into flour. Roller mill technology could entirely remove the bran and the germ of the grain, leaving behind only the endosperm. This type of flour, which was deemed highly desirable at the time, is referred to as “refined” because the roller mill extraction may also remove the associated B vitamins, vitamin E, omega-3 and omega-6 fats, fiber, and minerals that are naturally found in wheat.[22] This was, chronologically, our second major refined, nutrient-deficient food, with refined sugar having been the first. Today, wheat accounts for 20 percent of the world’s diet.[23] By 2005, Loren Cordain, S. Boyd Eaton, and colleagues had found that 85.3 percent of the cereal grains consumed in the US, particularly wheat, were “highly processed refined grains.”[24]

Also introduced in 1880 were the first commercially available seed oils, generally referred to today as “vegetable oils.” The first of these was cottonseed oil.[25] This was soon followed by the hydrogenation and partial hydrogenation of cottonseed oil, producing the first ever artificially created trans fat. The latter was introduced by Proctor & Gamble in 1911 under the name “Crisco,” which was marketed as “the healthier alternative to lard … and more economical than butter.”[26] This first commercially produced trans fat remains on the market today. The so-called vegetable oils, along with Crisco, would gradually supplant animal fats, such as butter, lard, and beef tallow. In fact, it was the manufacturers’ intent to undersell the more expensive animal fats that had traditionally been used in cooking.

Loren Cordain and colleagues showed that, in 1900, the consumption of olive oil, essentially the only edible oil available at that time for most people, would have been in the range of 0.5 pounds per person per year.[24] By 2005, however, the average American was consuming 86 pounds of added fats and oils per year, nearly 86 percent of which was vegetable oils and related products (shortening, margarine, cooking oils, etc.).[27] The remaining 14 percent was butter, lard, and edible tallow. Thus, in 1900, 99 percent of the added fats in cooking were animal fats such as butter, lard, and beef tallow, whereas by 2005, that number had dropped to a mere 14 percent.

Sugar, our final major nutrient-deficient, processed food ingredient, had ever-increasing consumption from the 17th century until 1999, after which consumption decreased slightly. Following his historical research on the subject, obesity researcher Stephan Guyenet, PhD, wrote: “Wrap your brain around this: in 1822, we ate the amount of added sugar in one 12 ounce can of soda every five days, while today we eat that much sugar every seven hours.”[28] He found that Americans consumed 6.2 pounds of sugar per person per year in 1822, which rose to a high of 107.7 pounds per person per year by 1999. This is a 17-fold increase in the consumption of sugar during that period of time.[28] In 1999, this amounted to an average consumption of 32 teaspoons per person per day.[29]

By 2009, 63 percent of US food consumption was made up of processed, nutrient-deficient, potentially toxic foods – that is, those containing refined grains (mostly refined wheat flour), vegetable oils, trans fats, and sugar.[30] This is a recipe for metabolic disaster – the same recipe that has led to an epidemic of heart disease, cancer, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and, in my opinion, AMD.

Synthetic vitamins – will they rescue patients from AMD?

More often than not, synthetic vitamins – i.e., those that come in pills, potions, bottles, and “fortified” foods – fail to deliver the intended results. The fundamental scientific literature is riddled with failures in this regard, as evidenced by recent lectures on this subject by Howard Sesso, ScD, MPH, at the Harvard School of Public Health,[31] and Jeffrey Tice, MD, at the University of California San Francisco’s Department of Medicine.[32]

But would synthetic vitamins, which I differentiate from those found in whole foods, be effective in preventing or treating AMD? With regard to the prevention of AMD, the Cochrane Collaboration evaluated four randomized controlled trials that included some 62,520 people. The results? In the words of the Cochrane Review authors, “People who took these supplements were not at decreased (or increased) risk of developing AMD.” Their final conclusion: “There is accumulating evidence that taking vitamin E or beta-carotene supplements will not prevent or delay the onset of AMD. There is no evidence with respect to other antioxidant supplements, such as vitamin C, lutein, zeaxanthin, or any of the commonly marketed multivitamin combinations.[33]

The next question is: Do synthetic vitamin/multivitamin supplements help delay progression of AMD that is already established? The Cochrane Collaboration found that there were thirteen randomized controlled trials that attempted to answer this question. Of those thirteen, twelve showed no benefit. The Cochrane study reported, “The review of trials found that supplementation with antioxidants and zinc may be of modest benefit in people with AMD. This was mainly seen in one large trial [AREDS] that followed up participants for an average of six years. The other smaller trials with shorter follow-up do not provide evidence of any benefit….Although generally regarded as safe, vitamin supplements may have harmful effects.”[34]

The one trial where synthetic vitamins showed a benefit, the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS, or the AREDS 1 Trial), published in 2001, evaluated some 3,640 subjects, 55 to 80 years of age, who consumed either a combination of vitamins E and C, beta-carotene, zinc, and copper or a placebo. The experimental group that received the supplements had a 25 percent reduced rate of progression of intermediate AMD to advanced stages of AMD over a period of five years.[35] In other words, one out of four subjects consuming the AREDS formula supplements saw a benefit. The AREDS 2 trial sought to determine whether the addition of the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin, the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA, or both might further reduce the progression of AMD. In the authors’ own words, “Addition of lutein + zeaxanthin, DHA + EPA, or both to the AREDS formulation in primary analyses did not further reduce risk of progression to advanced AMD.”[36]

So, the AREDS formula supplement appeared to benefit one in four patients who would take them over a period of five years, at least according to this one trial. Recall that the other twelve trials, all of which were shorter in duration, found no benefit to taking the supplements. In general, because of the AREDS study, perhaps most ophthalmologists have recommended the AREDS formula vitamins, as I once did as well. But ophthalmologist Carl Awh, MD, and colleagues have assessed the AREDS results based on genetic profiles. They determined that those people with certain genetic profiles (high CFH and low ARMS2, genetic variants that can impact the innate immune system), which was 13 percent of the studied population, had a 135 percent higher chance of progressing to advanced stages of AMD – if they took the AREDS supplements.[37,38] This is a more than doubling of the rate of progression by taking the supplements. Now what?

AMD prevalence and a Westernized diet – original research

To evaluate the effect of Westernization of the diet on the development and prevalence of AMD, my colleague Marija Stojanoska, MSc, and I mined the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) databases for data on processed food, sugar, and vegetable oils. We then plotted that data against AMD prevalence in 25 nations.

In this article, three representative graphs for three nations will be presented. Note that we have separated vegetable oils into “harmless vegetable oils,” which are the saturated oils (coconut, palm, and palm kernel oils) plus olive and flaxseed oils, and “harmful oils,” which are the oils containing the most polyunsaturated fats (soybean, corn, canola, cottonseed, sunflower, safflower, rapeseed, grapeseed, and rice bran oils). Those oils deemed to be of intermediate risk, due to the presence of both polyunsaturated and monounsaturated components, include peanut, sesame, high oleic sunflower, and high oleic safflower oils. These latter oils were categorized among the “harmful oils”; however, their usage is relatively limited in most Western cultures, and there is significant evidence that peanut and sesame oils are far safer than the others, as they have been consumed by Asian cultures with a high degree of tolerance for many decades.

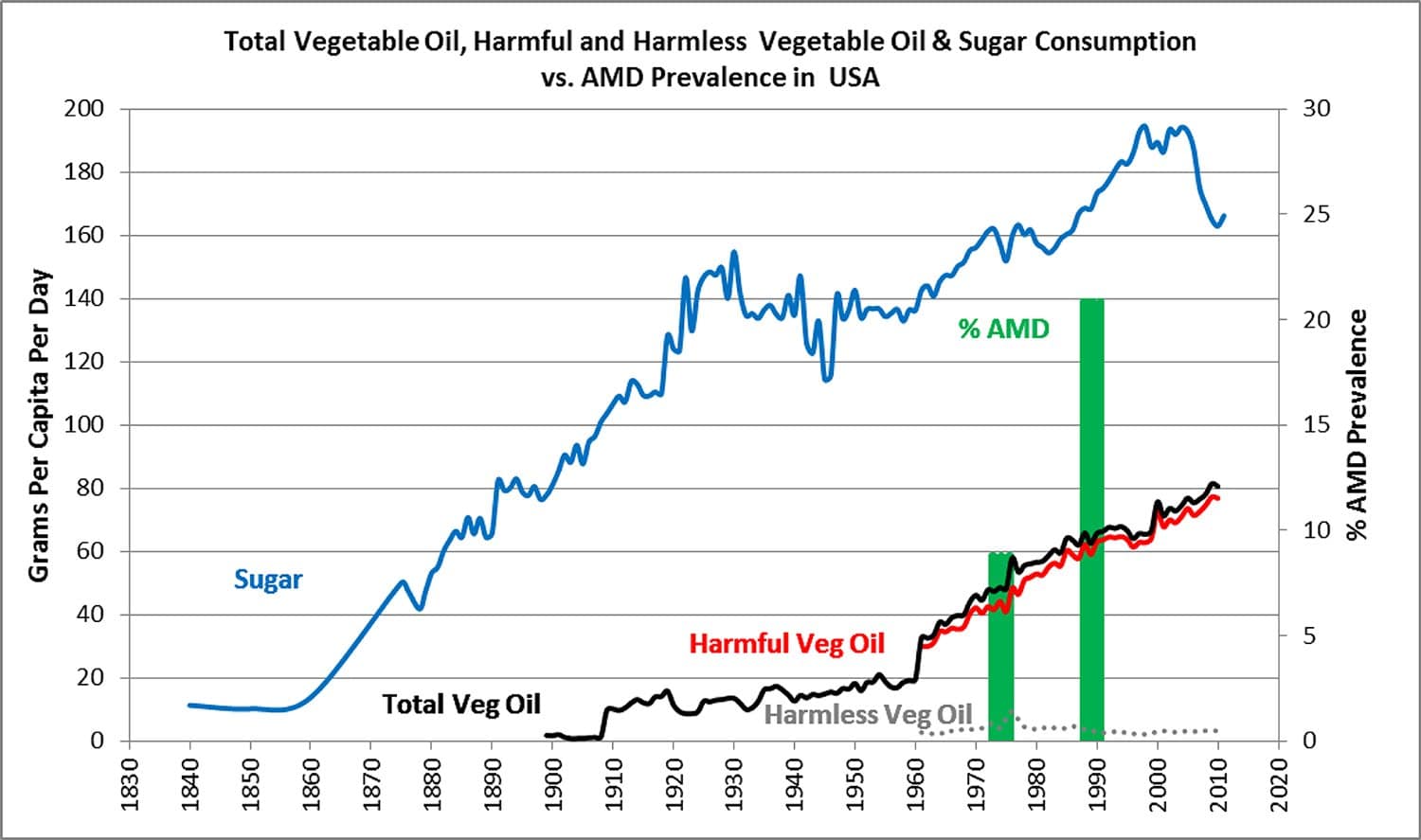

Below is the correlative data for sugar and vegetable oil consumption and AMD prevalence in the US:

Note that total vegetable oil consumption per person was around 2 grams a day from 1900 until about 1909 and then jumped up to 10 grams/day and climbed from that point forward, eventually reaching 80 grams/day by 2010. Sugar consumption was already at about 80 grams per day by 1900, climbing to a high of nearly 200 grams/day by 1999. As you will recall, AMD prevalence was negligible from 1851 until the 1930s and, as one can see from the graph, was at epidemic proportions by the 1970s and thereafter.

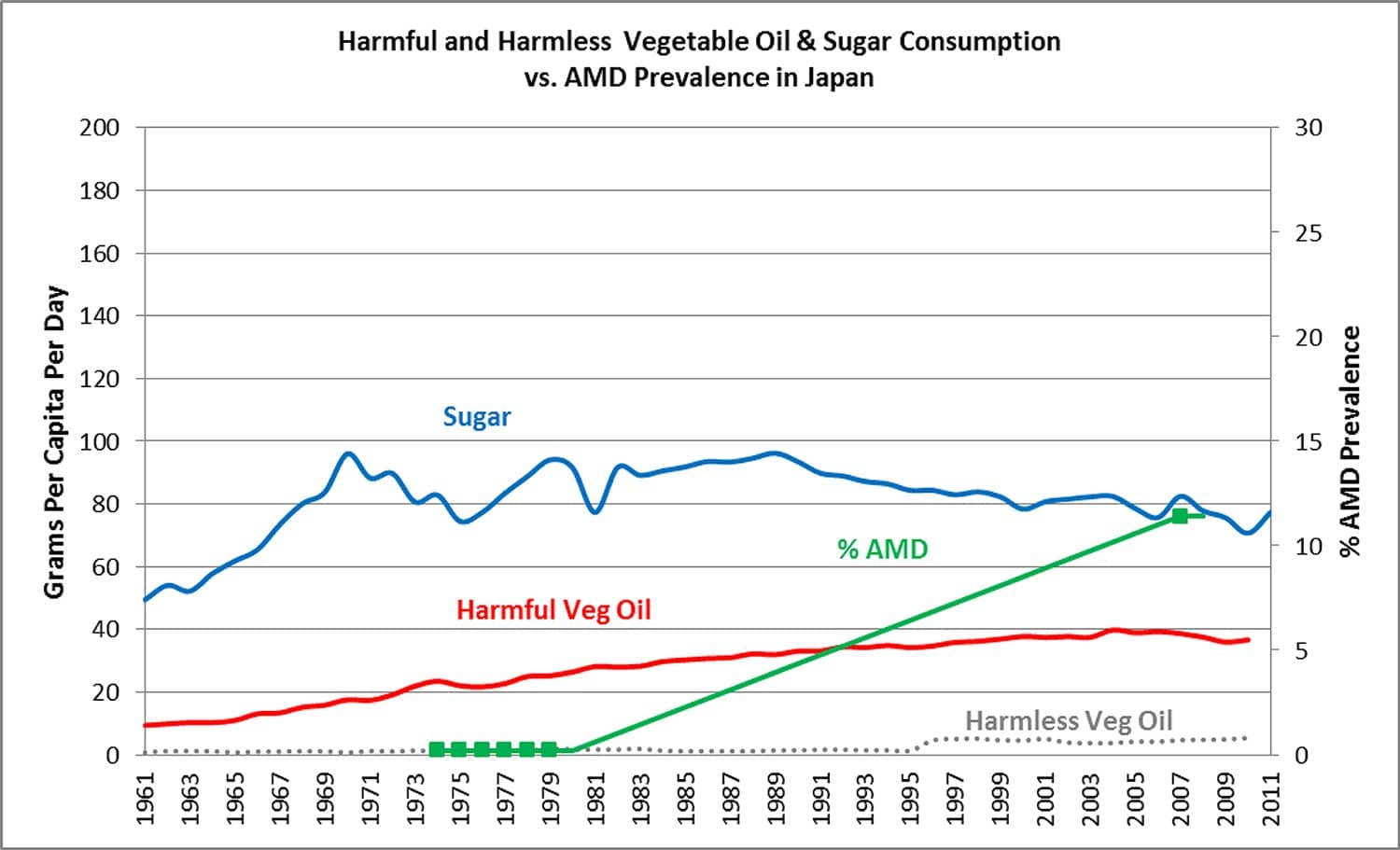

Japan is perhaps one of the greatest examples of this trend. We see rapid Westernization of the diet in the past five decades and, within a period of just under 30 years, AMD rose from the status of extreme medical rarity to a disease of epidemic proportions. Note that the consumption of harmful vegetable oils rose from 1961 onward, increasing about 4.5-fold between 1961 and 2005. Sugar consumption rose from approximately 50 grams per day in 1961 to over 90 grams a day by the late 1960s, and remained nearly at that level through 2011. Westernization of Japan’s diet was associated with a 57-fold increase in the prevalence of AMD in under 30 years!

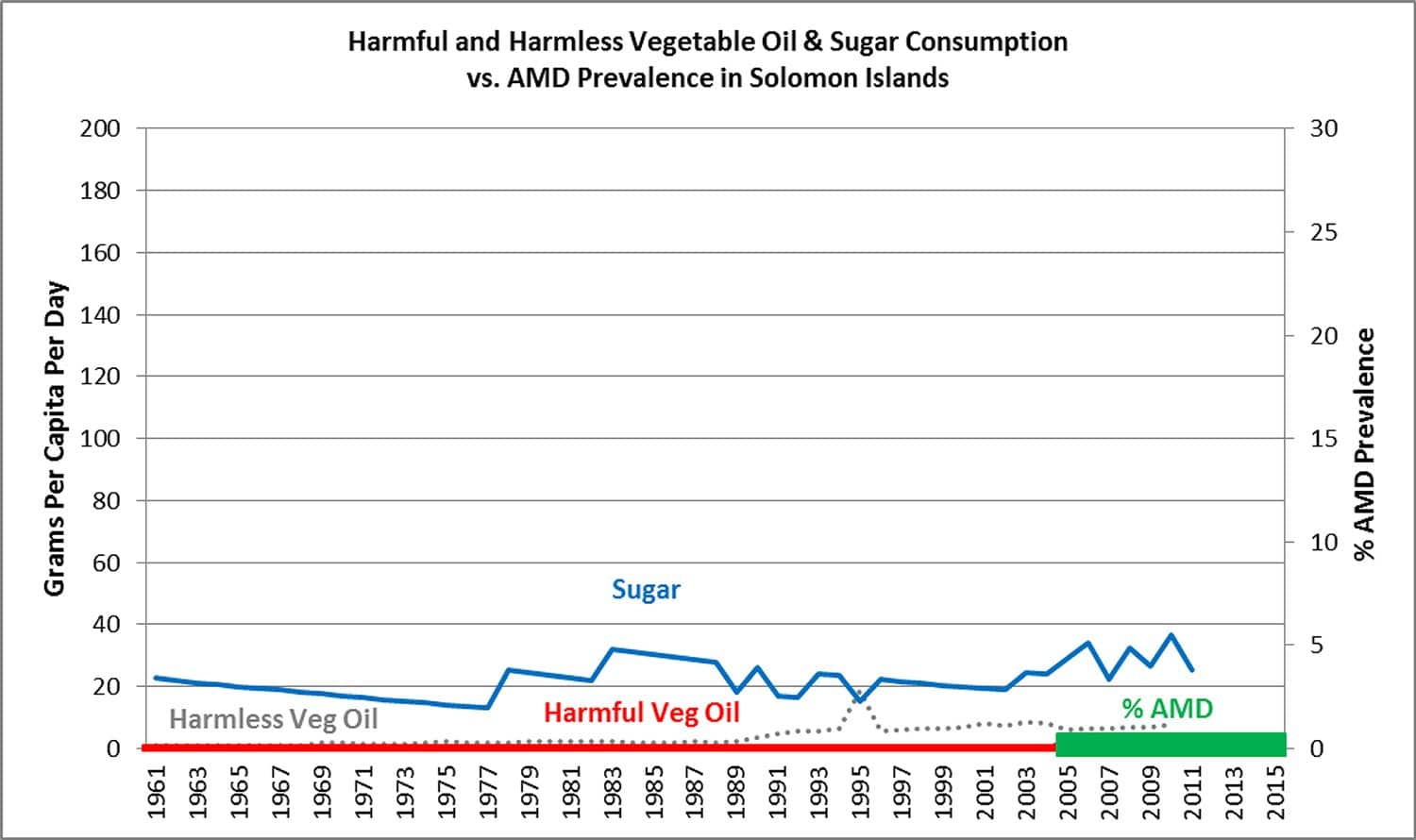

In the Solomon Islands, sugar consumption from 1961 onward has remained extremely low at around 20 grams per day, while harmful vegetable oil consumption remains at almost negligible levels. The prevalence of AMD has been approximately 0.2 percent – that is, almost nonexistent – from 2005 to 2015.

Conclusions and dietary recommendations

We’ve seen that, historically, macular degeneration was an extreme medical rarity from 1851 until the 1930s. During that period, three of our four major nutrient-deficient, processed food elements were introduced – refined white flour in 1880; polyunsaturated vegetable oils, also in 1880; and trans fats in 1911. Consumption of sugar, our fourth nutrient-deficient, processed food element, was on the rise. By the 1930s, macular degeneration was on the radar of ophthalmologists as a significant entity. By the 1970s, AMD was at epidemic proportions in the US and UK, and it has reached similar levels in many nations since then.

Every shred of evidence that I can find supports the hypothesis that it is the displacing foods of modern commerce that are the primary and proximate cause of macular degeneration. The prevention of this disease – as well as the treatment – can be accomplished by removing those elements from the diet and consuming only elements of our own native, traditional diets.

This would mean one should consume a diet rich in meats, fish, eggs, fruit, vegetables, some nuts and seeds, and, perhaps critically, some “sacred” foods of our ancestors, such as beef or chicken liver, fish eggs (roe), and/or extra virgin cod liver oil, plus possibly high-vitamin butter oil or pastured butter. My preference is to choose the wild or pastured versions of animal meats and eggs whenever possible, and organic fruits and vegetables, if affordable.

As for the AREDS formula vitamins, I advise against them, in favor of an ancestral diet. Finally, in my humble opinion, macular degeneration should no longer be called “age-related macular degeneration” (AMD) but rather “diet-related macular degeneration” (DMD).

Editor’s note: Supplements (even natural ones) can never replace or make up for a poor diet, and if such a diet is the root cause of disease, it should be addressed first and foremost. We agree with Dr. Knobbe that much of the scientific literature does show poor outcomes with supplements. In that regard, we have found that a great deal of research is carried out with inadequate doses, inactive forms of nutrients, and where other deficiencies prevent the study nutrients from working. In addition, many studies are too small and of too short a duration. Clearly, more quality research is needed in this area.

In our opinion, Dr. Knobbe has uncovered an important connection between diet and age-related macular degeneration that has the potential to prevent hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people from progressing to the advanced stages of this disease.

About the Author

Chris A. Knobbe, MD, is an ophthalmologist and Associate Clinical Professor Emeritus, formerly of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, in Dallas, Texas. Dr. Knobbe is the founder and president of Cure AMD Foundation™, a nonprofit, charitable organization, with the goal of eradicating macular degeneration on a global scale. He is also author of the book Ancestral Dietary Strategy to Prevent and Treat Macular Degeneration through the website CureAMD.org. He may be reached directly via the contact form at CureAMD.org, or at [email protected].

REFERENCES

- Van Bol L, Rasquin F. [Age-related macular degeneration]. Rev Med Brux. 2014; 35(4):265-270.

- Egan KM, Seddon JM. Age-related macular degeneration: epidemiology. In: Albert DM, Jakobiec FA (eds.). Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology: Basic Sciences. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Co.; 1994.

- Wong WL, Su X, Li X, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014; 2:e106-116.

- Klein R, Klein BE, Linton KL. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1992; 99:933-943.

- Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya’ale D, et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004; 82:844-851.

- Sun C, Klein R, Wong TY. Age-related macular degeneration and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116(10):1913-1919.

- Klein R, Deng Y, Klein BE, et al. Cardiovascular disease, its risk factors and treatment, and age-related macular degeneration: Women’s health initiative sight exam ancillary study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007; 143(3):473-483.

- Cheung N, Wong TY. Obesity and eye diseases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007; 52(2):180-195.

- Maralani HG, Tai BC, Wong TY, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2015; 35(3):459-466.

- Muehlenbein MP (ed.). Human Evolutionary Biology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2010:491.

- Cordain L. The Paleo Answer. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 2012.

- Albert DM, Edward DD (eds.). The History of Ophthalmology. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Science, Inc.; 1996.

- Hutchinson J, Tay W. Symmetrical central choroido-retinal disease occurring in senile persons. R Lond Ophthalmic Hosp Rep J Ophthalmic Surg. 1874; 8:231-244.

- Haab O. Zentralblatt fur prakrische Augenheilkunde. 1885; 9:383-384.

- Haab O. Atlas und Grundriss der Ophthalmoskopie und ophthalmoskopischen Diagnostik. [Atlas and outline of ophthalmoscopy and ophthalmoscopic diagnosis.] Munchen: Lehmann; 1895.

- Haab O. Ueber die Erkrankung der Macula lutea. [On the disease of the macula lutea.] Siebenter Periodischer Internationaler Ophthalmologen-Congress, Heidelberg. 1888:429.

- Keeler CR. A brief history of the ophthalmoscope. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, London, UK. Optometry in Practice. 2003; 4:138.

- Duke-Elder WS. Recent Advances in Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: Blakiston’s Son & Co.; 1927.

- Duke-Elder, WS. Textbook of Ophthalmology – Duke-Elder, Vol. III, Diseases of the Inner Eye. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby Company; 1940:2372 – 2373.

- Kahn HA, Leibowitz HM, Ganley JP, et al. The Framingham Eye Study I. Outline and major prevalence findings. Am J Epidemiol. 1977; 106(1):17-32.

- Knobbe C. Cure AMD – Ancestral Dietary Strategy to Prevent & Reverse Macular Degeneration. Springville, UT: Vervante Corporation; 2016:98-103.

- Slavin JL, Jacobs D, Marquart L. Grain Processing and Nutrition. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 2001; 21(1):49-66.

- Brenchley R, Spannagl M, Pfeifer M, et al. Analysis of the bread wheat genome using whole genome shotgun sequencing. Nature. 2012; 491:705-710.

- Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, et al. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005; 81:341-354.

- Nixon HC. The rise of the American cottonseed oil industry. Journal of Political Economy. 1930; 38(1):73-85.

- Proctor & Gamble. A Company History: 1837-Today. 2006. https://www.pg.com/translations/history_pdf/english_history.pdf.

- USDA Economic Research Service. Dietary Assessment of Major Trends in U.S. Food Consumption, 1970 – 2005. Economic Information Bulletin No. 33. March 2008.

- Guyenet S. By 2606, the US diet will be 100 percent sugar. Whole Health Source: Nutrition and Health Science. Feb. 18, 2012. http://wholehealthsource.blogspot.com/2012/02/by-2606-us-diet-will-be-10….

- USDA Economic Research Service. Profiling Food Consumption in America. In: Agriculture Fact Book. ND. Available at: http://www.usda.gov/factbook/chapter2.pdf.

- USDA Economic Research Service. U.S. Food Consumption as a % of Calories. 2009. http://www.healthyschoolfood.org/docs/color_pie_chart.pdf.

- Sesso H. Food and Vitamins and Supplements! Oh My! – Longwood Seminar. Harvard Medical School. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9E8bUIEsIo. Published March 8, 2013.

- Tice J. Vitamins and Supplements: An Evidence-Based Approach. University of California Television. http://www.uctv.tv/shows/Vitamins-and-Supplements-An-Evidence-Based-Appr…. Published October 29, 2013.

- Evans JR, Lawrenson JG. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for preventing age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012. Issue 6.

- Evans JR, Lawrenson JG. Antioxidant vitamins and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012. Issue 11.

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001; 119(10):1417-1436.

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research Group. Lutein + zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids for age-related macular degeneration: the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013; 309(19):2005-2015.

- Awh CC, Lane AM, Hawken S, et al. CFH and ARMS2 genetic polymorphisms predict response to antioxidants and zinc in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol. 2013; 120(11):2317-2323.

- Harrison L. Supplements to slow macular degeneration may backfire. Medscape. August 13, 2014. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/829860.

Published in the Price-Pottenger Journal of Health & Healing

Summer 2017 | Volume 41, Number 2

Copyright © 2017 Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation, Inc.®

All Rights Reserved Worldwide