Access to all articles, new health classes, discounts in our store, and more!

Cod Liver Oil: A Historical Perspective

Oil from the liver of Gadus sp. (particularly G. morhua, or Atlantic cod) has helped humankind for centuries – in the tanning of hides, as a fuel for lamps, in liquid soaps, and even as a base for the red ochre paints frequently used on buildings in the picturesque fishing villages that dot the shores of the northern Atlantic Ocean.

Cod liver and its oil have also long been used as foods in this region, as can be seen in traditional dishes such as Norwegian mølje, made from separately cooked cod flesh, liver, and roe, with drizzles of the fresh oil. The Russian zakuski tables – sumptuous buffets of hors d’oeuvres – often included salat iz pecheni treski, a salad featuring cod liver and its oil. Dishes using various parts of the cod, such as the heads, stomachs, and even the roe stuffed with the livers, were common in Newfoundland, Scotland, Iceland, and other Northern European cultures – with the oil adding flavor and a nutritional boost.

History of cod liver oil as an internal remedy

Folklore and tradition tell us that cod liver oil has also been used therapeutically in poultices, salves, and ointments by people indigenous to those areas, and written records document its use in the last few centuries. English doctor Samuel Kay of the Manchester Infirmary is credited with being the first to introduce the internal medical use of cod liver oil (from Newfoundland), around 1776.1 Thomas Percival and Robert Darbey, also doctors at the infirmary, chronicled its spectacular effects in the treatment of chronic rheumatism, and Percival reported their results to the Medical Society on October 7, 1782. Experiments and observations by other doctors, especially ones in Germany, followed.

By the 1830s, cod liver oil was also being used to treat tuberculosis,2 rickets,3,4 malnourishment, osteomalacia (softening of the bones), and some eye conditions.5,6 Its popularity continued to grow in the next century, as the health of the general population improved, no doubt due to a combination of factors, including a better understanding of nutrition and hygiene.

The two world wars hampered the importing and exporting of cod liver oil, resulting in reduced supply throughout the European continent. The precious oil was understood to be a nutritional powerhouse, containing ample amounts of vitamins D and A, that could help with wartime malnutrition in children. In 1943, Pope Pius XI inquired about the possible procurement of Newfoundland cod liver oil “to be kept at [the Vatican’s] disposal so it can be distributed at the end of the war in those regions where the health conditions of poor children demand it.”7 As a result, six tons of the oil were shipped to continental Europe in 1946.

Author and journalist Mark Kurlansky reports that during World War II, the British Ministry of Food “provided free cod-liver oil for pregnant and breast-feeding women, children under five, and adults over forty…. The British government, believing that the oil had produced the healthiest children England had ever seen, despite bombings and rationing, continued the program until 1971.”8

Legacy of Dr. Weston A. Price

Price traveled the world in the 1930s, searching out indigenous peoples who maintained their traditional diets and comparing their health with that of groups who had been exposed to modern, processed foods.9 Without exception, those groups who maintained their traditional diets were healthier than their modernized counterparts. One of Price’s important findings was that traditional diets – rich in foods from animal sources, such as eggs, organ meats, dairy products, and fish, with their abundant fat-soluble vitamins and unidentified “activators”- contained much higher levels of vitamins A and D than the modern diets of the US and Europe. To address the shortcomings of contemporary diets, Price recommended nutritional supplementation with cod liver oil, as well as avoidance of processed foods.

Just as myriad uses for cod liver oil have been discovered since the first fish liver was rendered, so have many methods of extracting the oil. Of course, these various processes result in different types of oil. Although Price conducted numerous experiments with cod liver oil, his most well-known published works do not mention specific brands or manufacturing processes. This has left much room for speculation about what type of cod liver oil he used. Fortunately, his unpublished work housed in the research archives of the Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation sheds some light on this, as will be discussed later in this article.

Which type is best?

Discussion about which process results in the best quality of oil is not new. As early as 1841, questions were being asked about the differences between various types. That year, John Hughes Bennett produced a treatise on cod liver oil, in which he described four types of oil (white, yellow, red, and brown) and their traditional preparation methods.10 Pale (light-colored) oils—those most commonly marketed for internal use—were obtained by cooking fresh livers with water at low temperatures, after which the oil was strained and filtered. The Scots macerated the livers in cold water, then heated them just until the pale oil separated out. In Ireland, the livers were heated in iron pots, then the pale oil was expressed. The process was repeated with the remains, resulting in a secondary brown oil. Bennett’s inclusion of testimonies on the benefits of cod liver oil from European doctors has been credited with furthering its acceptance among the population at large.

In 1839, Dr. Robley Dunglison, a British-born doctor who became the personal physician to several US presidents and was later known as the “Father of American Physiology,” wrote in his book New Remedies about the introduction of cod liver oil therapy to England.11 In the first edition, he referred to Thomas Percival’s report,11 and by the fourth, he had expanded the information, commenting on Dr. Samuel Bardsley’s 1807 published update on the Manchester Infirmary treatment.12 In 1835, reported Dunglison, a monograph penned by another noted doctor had upheld the experiments and observations of nearly a dozen English and Continental doctors and scientists, showing that cod liver oil was “a remedy of great and specific efficacy” for rheumatism.12(p457)

Dunglison described several methods of extraction, one of which involved slicing fresh livers and simply exposing them to the natural warmth of the sun, thus causing the first oil to run out. This is what we would call “extra virgin oil” today and, like olive oil, it was of varying shades of yellow and varying degrees of transparency. The clearest type of oil, wrote Dunglison, was ”more used [as a remedial agent] than the darker variety, although several physicians affirm, that they have found the latter more efficacious.”11(p339) He added, “If the livers are running gradually to putrefaction, the oil becomes of a chestnut brown colour…; and, again, after the oil has been obtained by the above methods, some can still be procured by boiling the livers.”11(p339-340)

Dunglison explained that the properties of the oil were said to differ among the varieties and stated, “According to Messrs. Gouzee and Gmelin the brightest oil ought to be employed internally; but MM. Trousseau and Pidoux think that the limpid [clear] oil has no medical virtue. They prefer either the second [the secondary pressing, or brown variety], or that which is obtained by ebullition [boiling], and has a disagreeable acrid taste.”12(p455)

In 1843, Ludovicus Josephus de Jongh, MD, of The Hague, Netherlands, published a lengthy discourse, titled in English The Three Kinds of Cod Liver Oil, in which he outlined what he understood at the time to be the main differences between three types of oil.5 He wrote with great specificity of each type and their effects on patients suffering from rheumatic ailments, sciatica, rickets, tuberculosis, diseases of the eye, cardialgia (pain in or near the heart), henicrania (a chronic headache disorder), and a plethora of other health conditions.

The 1895 book Cod-Liver Oil and Chemistry, by Frantz Peckel Möller, PhD, makes the point, however, that de Jongh’s results “were not particularly accurate,” with his measurements of some constituents being 100 times higher than what others found later.13 “Of course it should be remembered that the analysis of organic compounds was then in its infancy, and the methods he employed were very faulty,” wrote Möller. It should also be remembered that Möller was, at the time, the head of a firm that competed with de Jongh’s cod liver oil company.

Although de Jongh seemed to prefer the pale oils, he warned that unscrupulous manufacturers could bleach the secondary dark oil to pass it off as the more desirable (and expensive) pale type. His conclusions were not definitive beyond showing that all types of cod liver oil were beneficial in moderate use, with some taken internally and some used as an ointment.

Eventually, de Jongh traveled to Norway to procure and market what he claimed to be the best product available. A pamphlet he published in 1854 sang the praises of the low-heat, steam-extracted light brown oil, leading some reviewers to note that his conclusions may have been prompted by his business venture.14 Another review of this pamphlet stated bluntly that “in it gross errors and misstatements are put forth.”15

Nevertheless, his product was exceptionally successful – so much so that its name lives on today in a humorous Irish folk song popular on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. “Oh doctor, dear doctor, oh Dr. de Jongh, your cod liver oil is so pure and so strong,” cries a husband whose formerly ailing wife is filling his house from floor to ceiling with empty bottles from the cod liver oil she is consuming. “I’m afraid of me life, I’ll go down in the soil, if me wife don’t stop drinkin’ your cod liver oil.”16

Processing methods

Meanwhile, in Norway, chemist Peter Möller (father of Frantz Peckel Möller) invented a steam process for extracting fresh cod liver oil. He built a lined cauldron in which he steamboiled the fresh cod livers, greatly improving the oil’s quality.17 His invention received many awards in Norway and elsewhere. At the time of his death in 1869, no less than 70 processors were using his steam-rendering method.

However, in 1859, a competitor selling “pale Newfoundland cod liver oil” claimed to have the best product, quoting the assertion of Jonathan Pereira, MD, that “the finest oil is that most devoid of colour, odour and flavour.”18

The Proceedings of the Royal Colonial Institute for 1884-85 sang the praises of Newfoundland’s award-winning cod liver oil, explaining that the oil “from Norway is almost white, being bleached, and supposed by most persons to lose in that process its most beneficial properties.”19 The pure Newfoundland refined, straw-colored oil was said to be unbleached and used for medicinal purposes.

An 1895 report of cod liver oil manufacturer W. A. Munn’s visit to the Newfoundland factories stated that “as soon as the fish are landed the jelly-like, cream-colored livers are removed and taken to the oil works.”20 There, the fresh cod livers yielded the medicinal oil, then the residue was pressed to produce tanner’s oil. At the height of the season, with too many fresh livers to process immediately, the account continued, “the livers in excess are placed in barrels and allowed to putrefy in the sun, yielding a dark brown oil which is also used for tanning.”

An 1896 trade publication praised Munn’s Newfoundland refined cod liver oil, made by a freezing process that “produces an article rich in medicinal properties” that “will surpass the Norwegian article.”21 Much of the Newfoundland product was exported to England, where the taste for cod liver oil continued to grow.

By the end of the 19th century, there was no doubt that cod liver oil was beneficial. The big question, however, remained: Which type held the most benefit?

Vitamin potency

The early years of the next century saw the identification and isolation of vitamin A, followed shortly by the discovery of vitamin D. Both were found in cod liver oil, and this fact helped shed light on some, but not all, of its benefits. Even modern science cannot fully explain all the interactions and processes that make it so valuable.

Arthur D. Holmes, PhD, reported on the “vitamine potency” of different types of cod liver oil in a 1922 issue of Journal of Metabolic Research.22 The “vitamine A” content of crude cod liver oil, cold-pressed cod liver oil, and cod liver oil stearin was compared, as were their effects on laboratory rats. Holmes explained that “medicinal cod liver oil is obtained by ‘cold pressing’ high grade crude cod liver oil that has been prepared by rendering fresh cod livers under carefully controlled conditions. By the ‘cold press’ process, about 80% of the crude cod liver oil is converted into ‘pressed oil’ and 20% remains as cod liver stearin, a by-product of low commercial value principally used by soap manufacturers. After the ‘pressed oil’ is filtered it becomes ‘medical cod liver oil’ without further treatment.” These oils, he concluded, were all capable of meeting the vitamin A requirement of the growing albino rats, but he found that the pressed oil had a higher potency. It is worth noting that his “cold pressing” referred to the process of removing the slightly cooled, hardened stearin after the oil was rendered via the steam process.

Four years later, Holmes published an article in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal stating that cod liver oil had been used for two or three hundred years for the treatment of rickets, during which time various theories attributed its success “to its phosphorus or iodide content, to the unusual fatty acids that were liberated during digestion, and to its value as a source of energy.”23 Currently, he said, it was believed that cod liver oil was largely of value as a source of the essential fat-soluble vitamins.

In this publication, Holmes described only two types of oil processing. The “rotted” oil, he said, was prepared from livers undergoing decomposition and was “of a rather nauseating odor and taste … due to a number of secondary products such as butylamine, amalyamine, hexylamine, and dihydrolutidine, which may be produced by decaying cellular matter.”23 Holmes contrasted this with the “thoroughly modern process” that “involves the use of steam kettles, specially designed separators, brine cooled presses, and other equipment designed particularly for the manufacture of medicinal cod liver oil.” He observed, “Thus it is now possible to produce cod liver oil of a light yellow color, of low free fatty acid content possessing a wholesome odor and flavor and possessing a high vitamin potency.” Holmes asserted that this pale oil produced by “methods developed by science” was the better option. He also determined that American cod liver oil had a higher potency than Norwegian oil due, in part, to the fact that the Norwegian industry generally harvested cod during the spawning season, when the store of vitamins in the liver was depleted.

After reading Holmes’ vivid descriptions and discussion, it may not come as a surprise that when the article was published, he held the position of director of research for the E. L. Patch Company, an American manufacturer of medicinal cod liver oil.

Dr. Price’s research

During this time period, Dr. Weston A. Price was conducting numerous animal studies with cod liver oil. The results showed that some types of the oil were very beneficial to immunity and proper physical and mental development, particularly in regard to phosphorus and calcium metabolism regulation (positively affecting bone, dental, blood and brain health).24(p17-8) Yet he found that it could also cause great harm, especially when overused. He was careful to note “some dangers that are not usually recognized or properly emphasized in the literature.”9(p267)

Freshness and storage of the oil is important, he continued. Even though an oil may have a high vitamin content, if it is oxidized or rancid, it will not have the desired effects. “The available evidence indicates that fish oils [including cod liver oil] that have been exposed to the air may develop toxic substances.… Rancid fats and oils destroy vitamins A and E, the former in the stomach.”9(p267)

Overdosing with cod liver oil (and other fish oils), he cautioned, can be detrimental, possibly resulting in depression or paralysis, and he warned that “serious structural damage can be done to hearts and kidneys.”9(p267) In a paper published in the August 1932 Journal of the American Dental Association, he showed pictures depicting “progressive paralysis produced in a chicken and a rabbit, apparently by an overdose of cod liver oil.”25(p1348)

Despite these cautions, Price believed in the value of cod liver oil. He described numerous examples of its healing properties – when it is judiciously used – and provided assurance that “cod-liver oil can be given in moderate doses without injury and to great advantage.”26(p493) Except for special circumstances, Price recommended that cod liver oil be taken “with the meal rather than before or after, as it aids in the utilization of the minerals in the food.”26(p493) He also specified that children should seldom be given amounts greater than one teaspoonful per day for extended periods of time.

In addition, Price advised that cod liver oil can be taken with quality high-fat dairy products. He recommended high-vitamin butter oil, “mixed with about equal parts of a very high vitamin cod liver oil with variations in proportions according to clinical conditions. This combination is placed in a capsule containing about 0.6 gm (the 0 size). Two or three of these capsules are administered with each meal with a dietary adjusted to provide minerals and other nutritional factors, including the water-soluble vitamins.”25(pp1367-1368) He concluded, “Cod liver oil is available as a source of reinforcement of dairy products, plant and animal foods. While it has great value, it may contain and probably often does contain substances which are undesirable; therefore, it should be given in small doses, and only products of the highest natural vitamin content be used.”25(p1369)

High-vitamin butter oil from cows fed on early spring grass, taken with cod liver oil in equal parts, produced a symbiotic effect, Price found, with the mixture being “much more efficient than either alone,” making it possible to use smaller doses.9(p267) He explained, “Except in the late stages of pregnancy I do not prescribe more than half a teaspoonful [of the mixture] with each of three meals a day,” a dosage that precluded toxicity.

Activation

Although folk wisdom and some doctors had maintained for at least a century that cod liver oil was a cure for rickets, this knowledge wasn’t generally recognized throughout the medical world until the 1930s. Some physicians had noticed that sunlight and cod liver oil were beneficial in the treatment of rickets, but the reason for this was unclear. Harriette Chick, DBE, DSc, conducted clinical studies with rachitic children and adults suffering from hunger osteomalacia in war-ravaged Vienna between 1919 and 1922, and confirmed the value of both sunlight and cod liver oil in therapy.27

As this new knowledge became widespread, cod liver oil was advertised as “bottled sunshine” by one company, Squibb, and was heavily marketed to new mothers. The connection between cod liver oil and ultraviolet radiation inspired more studies over the next decades. Many of Price’s experiments involved “activated” cod liver oil—oil that was exposed to various types of radiant light (sometimes sunlight or light from mercury quartz lamps) for different periods of time.

In one paper, Price described the results of rubbing activated and raw (unactivated) cod liver oil on chicks.24 Based on his data, he hypothesized “that there is contained in cod liver oil, a factor which acts not only upon the alimentary canal or upon the foods taken into the canal, but is capable of acting upon living tissues to modify their absorption of calcium, and further, that this quality is enhanced by exposing the cod liver oil to ultraviolet radiation, in this case in the form of sunshine.”24(p17-15)

The results were not always beneficial, due to excessive ultraviolet exposure. In another paper, Price said that one minute of exposure on a bright summer day was equal to fifteen minutes of exposure on a dull winter day.28(p31) He cautioned, “Exposure for one hour to the noonday summer sun or to a mercury vapor quartz lamp produces a product which is distinctly harmful, and it would be better to use the raw cod-liver oil unactivated than to use this product.”28(p31)

Price also had personal experience with the detrimental affects of overactivation. “I have learned much from experimenting on myself, and one of the early safeguards that came from that source was secured as the result of severe headaches produced by taking cod-liver oil that had been exposed to ultraviolet rays from a mercury quartz vapor lamp for one half hour, even though the dosage was only a few drops.”28(p26)

His discussion of another animal experiment contained a warning that the oil “did not save the chickens if exposed to either sunshine or ultraviolet overlong, but, on the contrary, hastened their death. All the chicks receiving an overactivated product in all the groups died.”28(p17)

His studies showed that ordinary glass blocked the activation process, however, meaning that sunlight shining on cod liver oil through a window would not activate it.24

Dr. Price’s “excellent” oils

In addition to research papers, the Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation has, in their archives, some of Price’s original purchase records. With careful study, it is, in some cases, possible to determine what type of cod liver oil he used and recommended. For example, one of Price’s studies made reference to “Newfoundland cod-liver oil … [and] another excellent oil.”28(p25) On the next page, in a caption for one of the figures, he listed a brand name (Squibb), in addition to the Newfoundland oil.

Finding the listed manufacturing companies’ descriptions of their products from that time period cast light on what Price considered to be quality cod liver oil. Squibb, for example, described their oil as “cold pressed shore oil” in 1919 and “Norwegian cold pressed” in 1921. In making shore oil, the fish were caught by small boats near the shore and brought in the same day; the livers were then frozen and the oil pressed out.

Squibb’s published material stated that the cold Norwegian weather permitted the pressing of the fresh oil at a low temperature.29 After its rendering, the oil was kept in airtight containers and away from sunlight. The description made a clear distinction between the darker oil (“banks oil,” from livers allowed to decompose in barrels on larger boats that remained out for several days) and their oil—the lighter, fresh shore oil made from fresh livers. This light oil is what Price called “excellent oil.”

In Squibb’s patent application for their product, the process for rendering medicinal cod liver oil is detailed, with a description of a new process for protecting the oil from excess moisture, from contact with air, and, by extension, from oxidation. During this process, the document explains, the livers stay near a specific temperature so there is “no tendency for putrefaction or fermentation of the mass.”30

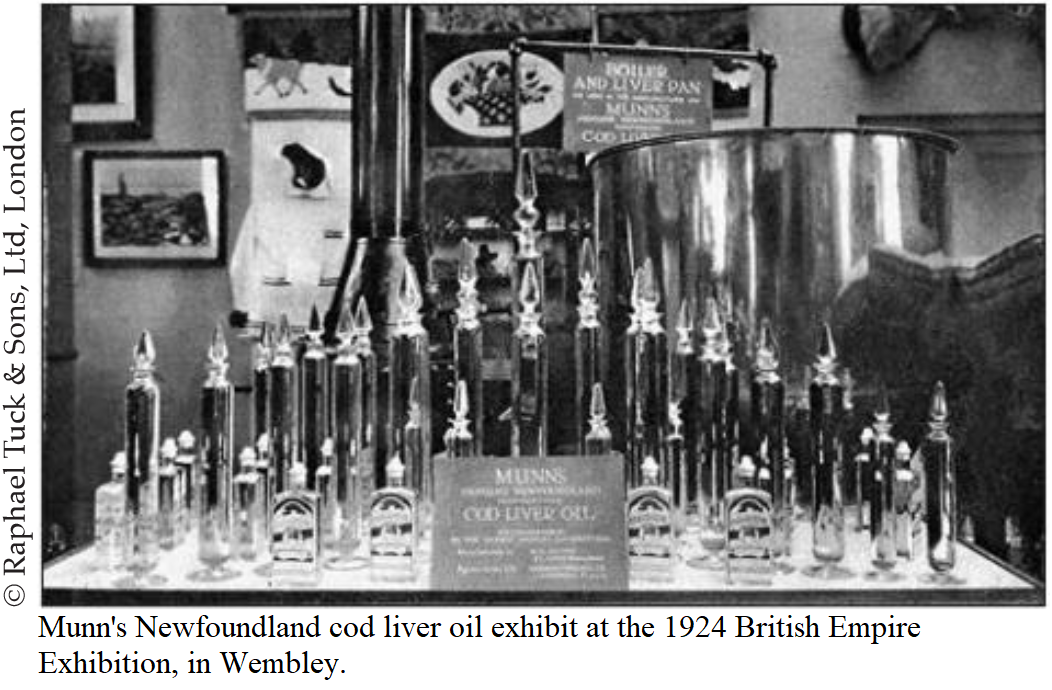

The other “excellent oil” Price mentioned was from Newfoundland, where medicinal cod liver oil processing had been regulated by the Department of Marine and Fisheries since August 1910. The department’s “Rules for Making Cod Liver Oil,” as published in 1924, dictated using fresh livers, steam processing them for thirty minutes, and dipping “the finest white oil” from the top within five minutes.31 The remaining oil from the “blubber” was considered unfit for medicinal purposes. As mandated by the regulations, the processing methods were the same for all Newfoundland cod liver oil at that time.

A postcard image (below) of Munn’s Newfoundland cod liver oil exhibit at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition shows cooking vats of the type described in the “Rules for Making Cod Liver Oil,” and tall glass containers of pale cod liver oil. This brand of pale oil, steam-rendered from fresh livers, is among those that Price ordered, and may be the “excellent oil” from Newfoundland.

A visitor to the exhibit remarked in the Newfoundland Quarterly that Munn’s “cod liver oil plant has attracted a lot of attention, together with his display of cod liver oil. The King and Queen [of England] thought that the latter looked most tempting and the King said it would be appetising if he had not still retained the vivid recollections of his youth!”32

For millions of children and adults, whether tiny infants, pregnant women, or King George V himself, cod liver oil boosted nutrition and health during the early 20th century, and this impressive nutritional powerhouse remains popular among those seeking optimal health today. Although it once seemed that time had erased the knowledge of which type of cod liver oil Price believed to be “excellent,” this information has again been brought to light.

The Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation archives include research and other papers of nutrition pioneer, Weston A. Price, DDS, author of Nutrition and Physical Degeneration. The PPNF research archives are available to members at: www.ppnf.org/resources/research-archives.

About the Author

REFERENCES

- Brockbank EM. Sketches of the Lives and Work of the Honorary Medical Staff of the Manchester Infirmary, from Its Foundation in 1752 to 1830 When It Became the Royal Infirmary. Manchester, England: University Press; 1904.

- Lakhtakia R. Of animalcula, phthisis and scrofula: historical insights into tuberculosis in the pre-Koch era. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013; 13(4):486-490. PMCID: PMC3836636.

- Trousseau A. Clinical Medicine: Lectures Delivered at the Hôtel-Dieu Paris. Vol. 2. Cormack JR, Bazire PV, translators. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston, Son & Co.; 1882.

- Guy RA. The history of cod liver oil as a remedy. Am J Dis Child. 1923; 26:112-116. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1923. 04120140011002.

- De Jongh LJ. The Three Kinds of Cod Liver Oil: Comparatively Considered with Reference to Their Chemical and Therapeutic Properties [translated from German]. Carey E, translator. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Blanchard; 1849.

- Rosenfeld L. Vitamine–vitamin. The early years of discovery. Clin Chem. 1997; 43(4):680-685. Reprinted by the Free Library. 2014.

- Archival Moments. Cod Liver Oil from Newfoundland. July 30, 1946. Posted July 25, 2013. Newfoundland and Cod Liver Oil. September 20, 1943. Posted September 19, 2013. http://archivalmoments.ca/tag/cod-liver-oil.

- Kurlansky M. Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 1998:154-155.

- Price WA. Nutrition and Physical Degeneration. 8th ed. La Mesa, CA: Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation, Inc., 2012.

- Bennett JH. Treatise on the Oleum Jecoris Aselli, or Cod Liver Oil, as a Therapeutic Agent in Certain Forms of Gout, Rheumatism, and Scrofula; With Cases. London, England: S. Highley; 1841.

- Dunglison R. New Remedies: The Method of Preparing and Administering Them; Their Effects on the Healthy and Diseased. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Blanchard; 1839.

- Dunglison R. New Remedies: Pharmaceutically and Therapeutically Considered. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Blanchard; 1843.

- Möller FP. Cod-Liver Oil and Chemistry. London, England: Peter Möller; 1895:c.

- Reviews. The Medical Times and Gazette. July 1 to December 30, 1854. 9:143.

- Waring EJ. Bibliotheca Therapeutica, Or, Bibliography of Therapeutics. Vol. 2. London, England: The New Sydenham Society; 1879:568.

- Cod Liver Oil. King Laoghaire Irish Ballads and Tunes. http://www.kinglaoghaire.com/lyrics/854-cod-liver-oil.

- Røde G, Schiøtz O. A Brief History of Flakstad & Moskenes, Lofoten Islands. http://www.lofoten-info.no/history.htm. Accessed July 5, 2015.

- The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art. 1859; 166(7):445. Advertisement.

- Pinsent J. Newfoundland – Our Oldest Colony. Proceedings of the Royal Colonial Institute (1884-85). 1885; 16:266.

- Newfoundland cod liver oil. Paint, Oil and Drug Review. 1895; 20(1):15.

- A new industry. Canadian Grocer. 1896; 10(1):28.

- Holmes AD. Studies of the vitamine of cod liver oils: the potency of crude cod liver oil, pressed cod liver oil and codliver stearin. Journal of Metabolic Research. 1922; 2:113.

- Holmes AD. Modern cod liver oil as a source of fat soluble vitamins. Boston Med Surg J. 1926; 194:714-716. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM192604221941603.

- Price WA. Calcium Metabolism in Health and Disease. Unpublished manuscript. From the Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation research archives. File W191.

- Price WA. Control of dental caries and some associated degenerative processes through reinforcement of the diet with special activators. (Reprinted from the Journal of the American Dental Assocation. 1932; 19:1339-1369). From the Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation research archives. File W133.

- Price WA. Transcript of a letter by Weston A. Price. In Nutrition and Physical Degeneration. 8th ed. La Mesa, CA: Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation, Inc.; 2012:490-494.

- Chick H. Study of rickets in Vienna 1919-1922. Med Hist. 1976; 20(1):41-51. PMCID: PMC1081690.

- Price WA. Newer knowledge of calcium metabolism in health and disease, with special consideration of calcification and decalcification processes, including focal infection phenomena. (Reprinted from the Journal of the American Dental Association. 1926; 13(12):1765-1794.) From the Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation research archives. File W107.

- Squibb’s Materia Medica. New York: ER Squibb and Sons; 1906:369.

- Nitardy FW. Production of cod liver oil. US patent 1,829,571. October 27, 1931.

- Rules for making cod liver oil. Public notice. Newfoundland Quarterly. 1924; Summer:52.

- The history of Newfoundland at Wembley. Newfoundland Quarterly. 1924; 24(3):9-14.

Published in the Price-Pottenger Journal of Health & Healing

Winter 2020 – 2021 | Volume 44, Number 3

Copyright © 2021 Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation, Inc.®

All Rights Reserved Worldwide